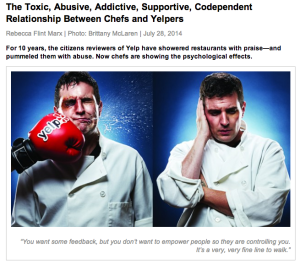

This morning I woke up to find this San Francisco magazine story at the top of Techmeme:

In great detail, it describes the rather fraught relationships restaurants especially have with the social rating service Yelp. Some of the mixed feelings revolve around the generally contentious nature of internet commenting itself.

In great detail, it describes the rather fraught relationships restaurants especially have with the social rating service Yelp. Some of the mixed feelings revolve around the generally contentious nature of internet commenting itself.

Ask any publisher or writer on the web. Your commenters can be your best friends but also your most feared critics:

“You want some feedback, but don’t want to necessarily empower people so they are controlling you.” Psychologically, he says, “it’s a very, very fine line to walk.”

How many of us, at various points, have sworn off comments, retweets and the like, writing them all off as trolls?

“Someone will just say something, and it’s like a knife all the way through,” Bililies says. “One that gets me especially is when they’re talking about the fact that the owner doesn’t care. I’ve put everything I have into this, and then to read that—I’m getting emotional now just relaying this—it just crushes you.” He takes a deep breath. “I’m now at a point where I try not to read Yelp anymore because it’s starting to affect my overall mental state.”

But there was another quote, that really stood out to me (emphasis mine):

“If two or three days go by and business sucks, I’ll go, ‘Shit, I got a bad review on Yelp.’” The cumulative effect is one of helplessness and supplication in the face of an unstoppable colossus. “They have you,” he says of the company and its users. “You’re in it whether you want to be or not, and that’s what’s so frustrating.”

In short, restaurants and other small business owners are chafing at the fact that an intermediary has stepped between them and their customers’ experience with their businesses. Before a customer has even put a foot in the door, they have an expectation of experience set by a third party. The long-term reputation of the business is curated and managed by that same third party, which may or may not be amenable to the business owner’s own attempts to manage said reputation. And yet, the business owner cannot disengage with said third party because it has become a primary driver of business and a way for new customers to even find the business.

What has been common online is now entering the offline world

Ask anyone who runs an online-only business if this feels familiar.

For years, online proprietors have had to deal with the fact that Google is literally the only game in town. Google doesn’t do online reviews (mostly) but it is the primary way people find you on the web. Quite simply, if customers can’t find you on Google, they can’t find you, period. And so if you don’t play well with Google, or Google doesn’t play well with you, you simply aren’t in the game.

“helpless supplication in the face of an unstoppable colossus”

This is a feeling online businesses know quite well. An entire multi-billion dollar industry (SEO) grew up to try to help businesses manage their relationship with Google (some would of course argue–game Google’s system) only to receive constant reminders that Google holds all the cards. You might find yourself ranking highly on Google one day and feel you have rightly earned all the traffic and status you’ve accrued… only to wake up the next day and see that some unfathomable new Google algorithm (with a cute sounding name like Panda or Penguin or Pigeon) has completely upended everything and taken away all your traffic.

In short, online businesses for years have been used to feeling like their livelihood and very existence is at the mercy of some inscrutable corporation, some unknowable Oz, that they must make sacrifices to in order to placate. And even then, it might all be pointless because the Gods are wrathful and unpredictable.

And now this same sort of thing is beginning to happen to off-line businesses as well.

It’s not just Google. Facebook is a major driver of traffic, as everyone knows. And this can be equally true for brick and mortar entities. But the algorithms of the news feed can be tweaked at Facebook’s discretion. Businesses were told for years to invest in Facebook pages and the accumulation of “likes” only to see those same pages recently devalued by Facebook itself. How many small businesses invested in Facebook pages as a cheaper, better way to have a web presence, only to learn the hard lesson that they “own” nothing about their user’s Facebook experiences?

There are plenty more examples of this same phenomenon seeping into other “real world” industries. Ask real estate agents if they can live without Zillow. (The Zillow-Trulia Merger Could Radically Reduce America’s Realtor Population). For a time, small businesses were convinced to give over their marketing budgets (and huge chunks of their margins, before the entire system collapsed because it was unsustainable, ultimately) to daily deal websites like Groupon. In major metropolitan areas, some of these same restaurants that complain about Yelp are also concerned about the fact that GrubHub and Seamless now manage their menus and delivery experiences on their behalf. And there are dozens of startups that are vying to make it easier to connect consumers with plumbers, repairmen, cleaning folk… even doctors, dentists and the like.

The pattern is always the same: some new player comes in and offers you, as a business owner or professional, a better way to find customers… by offering a better way for customers to find you. And they take a cut, which seems small, and certainly manageable, so long as the promised increase in sales pans out. But what is left unsaid is that they are also stepping between you and the customer in ways you might not anticipate. Once the business owner buys into this new system, they are not told that they could have no meaningful control over the mechanism of the system, which, upon reaching ubiquity, the business owner has no easy way to opt out of.

If you let someone manage your relationship with your customers, then who does the customer really have the relationship with?

In economics, the textbook definition of disintermediation deals with supply chains and distribution channels. But obviously, one of the many things that services like Google, Yelp, Zillow and others do is intermediate… step in between businesses and their customers. Not just add a new layer, but take over entire layers… of customer relationship management, of marketing, of delivering the basic service of a business itself.

There is no question there are efficiencies to be gained here, especially for consumers. As a loyal Seamless user, I can tell you it is much easier to just use the super-convenient Seamless app to order dinner deliveries rather than maintain the drawer full of menus that city-dwellers have used for decades.

But from the business-owner’s perspective, the long-term benefits of this process of intermediation are less clear. In the best-case scenario there is a future with increased sales, better margins and greater efficiencies. In the worst case scenario, the intermediary has effectively taken control of your market and eaten your value proposition. And you’ve ceded control of your business itself.

For years, online businesses have been told that they were foolish to begin with to cede so much power to sites like Google and Facebook. They’ve been told that any business built on someone else’s traffic wasn’t really their business to begin with. That’s a true, albeit, glib point. Because this is essentially what the online system has become: a churning morass controlled by 3 or 4 major gatekeepers. Who can be blamed for playing the game if it’s really the only game in town?

The question is, how will small businesses and offline retailers respond now that this system is coming to their game as well?

No Comment