Summary:

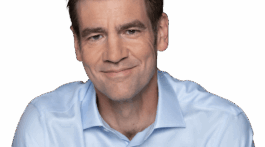

Aleks Totic was one of the original Mosaic engineers at the NCSA, responsible for the Mac version of Mosaic. They don’t call him “Mac Daddy” for nothing. He was then one of the 6 original programmers recruited by Marc Andreessen and Jim Clark to form Netscape. Aleks gives us some excellent behind the scenes anecdotes about both projects, and what it was like to head out to California to work on some crazy startup before doing something like that was “cool.”

A few fun nuggets of history we mention in the conversation:

- Click to hear Marc Andreessen ask, “What is global hypermedia?” back in 1993.

- The famous whiteboard. They packed up the truck and moved to

BeverlyMountain View - Original Mozilla t-shirt designs.

- 20-year old photos of the NSCP team.

Listen:

And here is a (not at all) edited transcript of the above interview:

Brian: You were born in Belgrade, in what was the former Yugoslavia, correct?

Aleks: Yes.

Brian: And I think that you were schooled around the world. You went to school in Kuwait? Is that correct?

Aleks: Yes, a British high school in Kuwait.

Brian: So, when did you come to the US?

Aleks: I came to US in 1984 because Yugoslavia would not accept my British high school diploma. So, I had to pick between some English-speaking country, and I thought Britain was too small. So I came to US. That was foolish.

Brian: Yeah, I heard that you ended up in upstate New York, and you thought that that was right outside of New York City.

Aleks: Yes. I didn’t realize how far away I was until we tried to go there by subway.

Brian: You ended up going to college first at BC [Boston College], in Boston?

Aleks: Actually, it was St. Bonaventure, upstate New York, was my New York City destination. Then I realized what a mistake I’d made. I asked my friends, “What was the most European city in the United States?” My friends said Boston, so I applied to Boston College. And that’s how I ended up at Boston College.

Brian: Were you doing Computer Science? What was your—

Aleks: Oh, yeah, yeah. Basically, I started computers in Kuwait ’cause when I moved there, I was a junior in high school, and I did not speak English very well. And I was also trapped at home 24/7, except for the bus that took me in from high school. So I asked my parents to buy me a computer that I saw at school and I loved it. And that was that.

Brian: Did it happen to be a Mac?

Aleks: No, no, that was too early. It was a Commodore 64.

Brian: Okay.

Aleks: I started coding, and I was like, “Now I know what I’m gonna do for the rest of my life.”

Brian: How did you pick up the name “Mac Daddy,” then?

Aleks: Oh, because when I was at BC, I started . . . Actually, I saw a Macintosh in Kuwait for the first time, but it was just too unaffordable. But when I was at BC, it was part of the Apple college program. So we had Macs. So I got a Mac, and started coding the Mac. And that’s how I got my first job, and that’s how I got a job at NCSA, too. So, all thanks to Macintoshes.

Brian: So your graduate school is University of Illinois.

Aleks: Yes.

Brian: How did you come to get the job at the NCSA?

Aleks: Well, I was not accepted on a scholarship, so I had to work to pay for my school. And NCSA had a great research assistantship that they asked me to do. So I joined them. It was really not a research internship. It was more like coding on demand. We were just hackers. They had a lot of interesting projects to work on.

Brian: Do you remember what you were working on at the time?

Aleks: Oh, I think it was called “PolyView”, which was . . . I can’t quite remember. There were several projects I was on, but it was some kind of 3D stuff on the Mac, mesh modeling, stuff like that.

Brian: Visualization programs.

Aleks: Yes. Oh, NCSA was heaven. They had all the toys, you know, from thinking machines to Crays, to Macs, to beautiful networks. It was awesome.

Brian: Including, obviously, super-fast hook-ups to the Internet. Do you remember when you first encountered the web at all?

Aleks: Well, I first encountered the web . . . I actually don’t remember the exact time. Well, being at NCSA, you were already on email. You were reading UseNet, so we were on the web before there was the web. And then Marc comes up, and he’s like, “Hey, I got this cool new toy. Check it out.” And that’s kinda, like, how we first encountered the web.

Brian: Do you remember hearing for the first time about the Mosaic project at all?

Aleks: Oh yeah. I was one of the kinda, like, hacker guys. I wouldn’t call it “hacker,” whatever. The guys who knew how to code. There weren’t too many of us, but we mostly lived in the basement of NCSA, and we coded a lot. And we always hung out together. You know, talking about coding, mostly. And so, how did I hear about it? So we were, I think . . . at that point in time, one of the projects finished, and Marc was looking for the next thing that he wanted to work on, and he found the web, so of course he told us. So it kind of happened pretty fast.

Brian: Marc and Eric Bina do their browser on X Window first, right? So when are you approached to start working on a Mac port?

Aleks: Well, I think very soon after the X-Browser was released, they said, “Hey, it’ll be really cool if this ran on everything.” So, as I was the best Mac guy around, and I was hanging out with these guys, I started working on it. It was me. And that’s how I became the “Mac Daddy.”

Brian: So there really wasn’t any sort of assigning of duties or anything, it’s just everybody . . .?

Aleks: No, no. This was basically a bunch of guys sitting in front of their computers all day long thinking stuff up.

Brian: And it’s not . . . these ideas come out of your interests, and so again, it wasn’t like . . .

Aleks: Well, NCSA had a mission. They had projects that we had to work on, and all that stuff. But you know, the cool thing is that their mission was very, well . . . you know, it was science and communication and this and that. So NCSA’s mission was very well-aligned with what Mosaic was going to do. When Marc discovered Mosaic . . . I mean, when Marc started the Mosaic project, I think we had just finished one of the other projects, I’ve forgot its name. So there was really nothing on his plate. So, Mosaic was discovered because he was looking for the next thing to do.

Brian: What was it like when Mosaic blows up? When, all of a sudden, this is . . . The internet’s still young. The web especially is still young, but it suddenly becomes the hottest thing around for people that are on the web?

Aleks: Well, the web was not that big. There’s several interesting things. One is, working with Marc in those days was pretty awesome. So we got really excited about this project right away, right? It was obvious that if it worked, it was gonna be big. We were like, “Oh, there could be newspapers on the net, and all this information can be out there for everyone! How phenomenal would that be?” Now, at the same time, it was not entirely obvious that that was what was gonna happen because the rest of the world saw it very differently. They saw a whole bunch of closed networks, such as AOL, CompuServe. I think Microsoft had their own Microsoft MSN. So what the rest of the computer industry was thinking about at that time was a whole bunch of closed networks. And initially, the web was mostly colleges, and almost every web address you went to was .edu.

Brian: Right.

Aleks: Right. So it was not obvious how big it was gonna get, but it was definitely growing at a very fast pace. There were more and more users all the time. It was really exciting. The coolest thing early on was— when we knew that we were on a threshold of something big—was when the New York Times published their first article about the web by John Markoff.

Brian: Right, it was on the front page.

Aleks: It was, I think it was on the front page. And the phone system crashed. There were so many people calling in that basically all the long distance lines into like Champaign-Urbana, or whatever, wherever we were, nobody could get through anymore. So at that point, we were like, “Wow, this is cool.”

Brian: So how does the NCSA . . . how do they feel about this project taking off? I’m kind of skipping ahead here to you guys leaving for Netscape, but I’m curious because a huge portion of this team does end up leaving. Is it because there’s some sort of friction with the NCSA? Has this gotten so big so fast? Or what happens there?

Aleks: So, we were very lucky. I think there were about six of us on the original team. And we kind of “got” the web. We got the meaning of what it was gonna be, and we were all very much on the same page. So we had this very strong . . . we were very good coders. We programmed all . . . we lived and breathed code in that basement. Marc was there all the . . . we were all just living there 24/7. And the cool thing . . . actually, the web, when it started, was actually highly addictive. Because for the first time: you released something, you had all these users. And the cool thing was that the users were around the world. So, nowadays, it’s kind of commonplace, but back then, it’s like, you would be working and your US users are going to sleep, but then you work alone for a little while, and then, boom, you have all these emails with your European users that are just waking up. So you were just running on adrenaline all the time because there was so much stuff to do, and . . .

Brian: Well, and also, when you push out a new feature, you can get feedback instantaneously.

Aleks: Oh, the feedback was instant. And all this stuff is taken for granted now. Back then, it was completely revolutionary. Back then, you used to ship software on CD-ROMs. So it was quite a rush. And the funniest . . . I mean, the coolest part, early on, was that Marc was the X guy. All the communications went directly to him. I was the Mac guy. Anybody having anything to do with the Mac browser, any bug, I would be responding to them personally. And the same was true for the Windows team. So there was this really intimate, crazy thing with tons of people talking to you, and you’re just one guy, right there, doing stuff. And you ship it . . . anyway, today it’s all quite common. Back then, insane. So what happens is, we have this project that becomes insanely popular. At the same time, this project has not, you know… NCSA is a kind of a government research lab. It’s a research lab that gets a lot of its funding from the government… the University, you know? And this project was not part of any particular grant. It was kind of originally budgeted out of the general budget. So there was no money coming in because of it. Of course, as soon as it got successful, that was going to change.

Brian: Right.

Aleks: So, instead of the original six-hacker structures, now the grown-ups are coming in and saying, “We need to run this as a serious project.” We get some help. There is some cool stuff. We get Colleen, who is like a really cool UI person, so we get a really cool new spinning globe, and this and that. But then, at the same time, you have a lot of people who have very different agendas and very different visions of what the web is going to be like. For example, one of the early ideas by higher-ups was that we should track everybody and send that data back to NCSA, because this is going to be the world’s greatest social study project.

Brian: They were thinking of it as a research project.

Aleks: Well, it was a research project. I mean, even Mosaic itself was a research project. But their vision, we were like, “That is insane. You can’t do that.”

Brian: Right. ‘Cause you guys have this completely different vision that’s so much broader than that.

Aleks: Exactly. We were like, you know, this is just the web. So, you know, there are all these other interesting things that we need to get done. We need the images, we need multimedia, we need, you know, whatever. A million different extensions need to get done, and this guy’s bugging us with some research project. We don’t like that.

The problem is, now, we’re starting to get bogged down. So, it becomes a fight of who is going to determine the future of Mosaic. Now, there’s business interests involved. People want to license it, this and that. And with the licensing, they would like you to implement a particular feature or work on their pet platform. So you’re starting to get into all these decisions about what the six of us are going—oh, and also there’s other people coming in and starting to code with us! And they’re not quite on the same fanatic level we are. For example, we were very good. And nowadays I feel a little bit more charitable towards my coworkers than at that time. But at that time, what I was thinking was, “Who are these people coming in and ruining all my code?”

Brian: Right. I think there’s a quote in one of the books that someone says that, you know, you had basically done the Mac version yourself, and then all of a sudden there’s all these new people assigned to you, and . . .

Aleks: Yes. Well—they’re not assigned to me! They’re my bosses!

Brian: Oh, even worse!

Aleks: Well, it’s not worse. It’s a collaborative relationship. But they’ve decided that Apple has just come up with a new voice recognition framework, so we’re going to add voice recognition to the web, and also make an even prettier spinning icon. I remember my first big release, 1.0, was… I had to release it right away. Because that new pretty spinning icon? It was leaking an icon every time it spun. So, if you started a long download, by the time you’re done with the download, you’d be out of memory. And that change went in two days before the release—over my big objections. And anyway… so it’s that kind of stuff. We were used to this insanely fast pace because we were all on the same page. We had a clear vision, and we were just going flat-out. And suddenly you have bureaucracy coming in.

Brian: Chris Wilson described that it was just personality conflicts, basically.

Aleks: Yeah, well, I . . . personality and the whole thing is like, we have this one vision of the web, and then . . . and our vision is just the pure Internet. We just want the browser. That’s the thing. And I think other peoples’ visions were different. They want something for NCSA. They want something for their company. Our vision is just, “We just want it. This is just awesome.”

Brian: So at some point, Marc Andreessen heads out to California. Do you recall how you heard that he was coming back? I’m referring now to the trip that Marc and Jim Clark make back to Illinois to recruit you guys.

Aleks: Yeah, so Marc goes to California, and he starts working at EIT, which is some kind of a server/web company. And we were all really sad because working with Marc is amazing. He was the leader. He was a natural leader. And we miss him. He was actually the voice that would always stand up to power at NCSA. He just wasn’t, you know. He was a very strong advocate for what we wanted. Without him, we’re doing pretty good coding work, but we can’t push it fast as we want. It’s more like now we’ve just become programmers. Before, we were more like a team on a mission. And Marc goes to California, and he’s no longer working on Mosaic. And we’re all very sad about this development because we’re like, “Marc, how can you leave this?” But we understand. He had to lead, and if couldn’t lead NCSA, he had to leave. And he’d just graduated. He graduated that January. I got my Master’s. He got his Undergrad degree. And so he did leave; came to California. Anyway, so we kept in touch. And then, I think he talked to us. He told us that he’d met Jim Clark. He was very excited about it, and then, I don’t know, one thing led to another, and he said, “You know, we’re not going to do Nintendo network. I think we’re going to do the web.” So, they flew in, and it was phenomenal. We got to meet Lou Montulli, and Jim Clark came in. We really didn’t know much about Jim Clark, but we trusted Marc. He gave us all these papers to sign. We just met him for one night. The next morning we all walked in and quit, and we said, “We’re going with Marc.” That was on Thursday. On Saturday, we were in California picking out the apartments, and a week later we moved out here.

Brian: That’s amazing. And there was no hesitation at all? You just knew right away that this was what you wanted to do?

Aleks: Well, we wanted to work on, you know, we wanted the web, the Mosaic, the browser. And Marc was the best guy to do it.

Brian: Did you make t-shirts or something that everyone signed?

Aleks: I did. I actually made t-shirts. I kind of had a feeling that this was coming, so I made t-shirts to commemorate the occasion. I got the girl who made our spinning icon, Colleen, to give us the original graphics, so, I printed these big t-shirts and everybody signed them.

Brian: So now you’re out in California, and is it back to . . . the band’s all back together. So is the working environment back to how you liked it now? You’re all working in the same direction. You’re working fast. You all have the same vision. Is it what you had hoped for?

Aleks: Yes. Well, now our vision has changed slightly, right? By this time, the stuff we worked on, Mosaic, was pretty entrenched. I mean, everybody loved Mosaic. Everybody used Mosaic. And here we are out there in California, and we’re like, “Will we ever be able to beat ourselves?” We’re basically racing against ourselves. And we’re like, “Yeah, but it’s gonna take some time, and they [the NCSA] might pull something together. This could be a real competition for a while.” So we come down here— and actually, an interesting thing about coming to California that might be relevant to the kids today is, back then, being a geek was very different from today. I don’t think it’s glamorous today, but it’s not weird. Back then, it was definitely weird. You felt weird being a geek. I mean, it was not common. And we were all misfits in one way or another. And so we come to California, and it’s like Mecca. You’re just driving the 101 and there is Sun, there is SGI, there is Oracle. And there is Fry’s where you can walk in and buy all kinds of stuff. It was mind-blowing. It was beautiful. I felt like I’d come home. So anyway, we come in, and we don’t know anybody around here. Everybody moved within a five-minute drive of the office. And we’d just start working. Oh, we’re back together. We have the same vision, but now, we also have Jim Clark and the backing. The other stuff is gonna happen to back us up and won’t hinder us. So, it’s kind of cool. We’re very excited.

Brian: Well, and now you can do it properly, right? Before, this was just a lark project, but now you can really do it the right way.

Aleks: Well, you know what, any time you code something for the second time, it’s a lot easier. And you can do it a lot better. And we have Lou Montulli, who is awesome. And there’s, like, all these other super-cool people that we’ve known about coming. So an interesting thing was that when we were doing Mosaic, we went to the first World Wide Web conference. There were 30 people there, total. So that’s how small the original web was. It was like, everybody who was anybody who was coding anything was in that room of 30 people. And when Netscape started, within months, half of those people are gonna be working with us. Everybody who had the same vision we did.

Brian: Right.

Aleks: Which was great. And also, we had no social lives of any kind, so we just kind of lived and— oh, and we have something to prove. We have to kill Mosaic.

Brian: That leads to the birth of Mozilla, yes.

Aleks: “Mosaic killer,” Mozilla.

Brian: Who was the person that came up with that concept or drew the Mozilla?

Aleks: Oh, I’m pretty sure Jamie drew the Mozilla.

Brian: Okay.

Aleks: Now, who came up with the name? I think it was Jamie Zawinski, but I’m not exactly sure.

Brian: Jamie Zawinski, okay.

Aleks: Yeah. But I think, you know, I don’t know. In my mind, I have no idea. I remember it happening like while we were walking to lunch one day.

Brian: In your memory though… So it’s: you don’t have a social life. You don’t know anybody out there. So the long hours and the sleeping under your desk, you guys don’t mind that at all at this point?

Aleks: No. No, well, yeah. That’s just what we do. What’s interesting is kind of reflecting upon this, it’s kind of like, all these things are completely new to us, and we are just doing it because . . . you know, we’re working around the clock because that’s what we used to do before. And you have users 24/7. Why not work around the clock? But looking in retrospect, it’s like four years later, five years later, the entire valley will be living the same lifestyle, which is funny. But those people actually have lives. We really didn’t have any lives outside of the office, so of course we’re gonna be at the office all the time. I mean, I had no furniture. Why should I ever go home?

Brian: So are you essentially doing the Mac version again? What are you working on?

Aleks: Yeah, I’m the Mac guy. Same thing. Same setup. We had three platforms, except Eric had moved and set up as… He’s now doing the parser. And we have Luke, who’s doing the networking. So we have a couple guys moving to cross-platform, and then we have the front-end guys. I’m the Mac guy. Somebody else was the X guy.

Brian: Do you remember when your beta finally launches, and you get to see the downloads come in, and things like that?

Aleks: Oh, absolutely. Before it launches, it’s just really exciting. It was like, I don’t know, how long did it take us? Five months? And we have all this really cool new stuff. We have wonderful offices. It was awesome. There’s people getting hired. The rest of the company seems to be humming, too, but we’re just battened down at our desk. It’s just really pleasant. We’re just working around the clock. But we also are joined by a lot of Silicon Valley veterans from Silicon Graphics and all around the valley, like J.G. I think Brendan was there already. I can’t remember how early he was. Anyway, so these guys are a little more savvy. So when we launched, for example, I think J.G. was the one who hooked it up. He had our FTP server, and when we announced it from WWWTalk, we had a different sound effect for different downloads. Each client got its own sound effect. So there was, like, a frog, smashed glass, and lightning I think for X, Mac, and Windows.

So everybody gets into this big, dark room. I think we released somewhere around, I don’t know, in the middle of the day, or maybe later. And we’re all sitting in this room just listening for the sounds. And as soon as our email goes out, within a minute, there’s some guy in Australia trying to download, and you hear the smashing glass. And then a couple minutes of silence. And then another “Croak.” Oh! And a cannon; there was a cannon. And then there would be a cannon.

And then it started getting faster and faster, and within six or . . . we were all just sitting there, drinking beer just coding a little bit, maybe, and just listening. And within five or six hours, there was just a cacophony of explosions and croaks and lightning and cannons. It was just awesome, because people were downloading it from all over the world. We were like, “Okay, we got something.” Everybody loved it.

Brian: You kind of touched on this a bit, but I mean, you’ve gone on to work at other start-ups. I think you worked at Epinions with Lou. Is that right?

Aleks: Yeah.

Brian: Being as how, you know, Netscape was not the first start-up in the world, but it was the first web start-up, and it did kind of set the template… Was it a different environment than other start-ups that you’ve been involved with? I mean, I guess it was ’cause you’re not following any template. You’re making it. But how would you compare Netscape to other start-ups you’ve worked on?

Aleks: Interesting thing. Early on in discussions with Marc over beer, and other guys, all the Mosaic guys, we… at that point, when we got into fights with our management, we were like, “You know, this government stuff is really annoying. People are in positions of power because of their titles. It’s not because of their coding. What would be really cool is just to have a purely commercial company like com dot com dot com… pure meritocracy based, and there was none of this government stuff. And it would be even cooler if we could just be on a big boat, just sail around the world.”

So that was one of our daydreams. And you know, dot com was not a common URL back then. And then you fast forward to the year 2000 and dot com is everywhere. It’s insane. So anyway, it’s like all your dreams have come true.

So how does working at Netscape compare to other start-ups? Well, I feel that Netscape was like a religious quest. It was: you’re changing the world. But not changing the world a little bit, like fundamentally. You felt it in a big way. You’re out there to destroy the existing order in many ways. And that was what the whole company was about.

The IPO, the press we were getting, it was kind of incidental. The thing we were building was the thing. That was what it was all about. It was not about us. It was like we were all on a mission. Netscape was truly a mission.

The other start-ups I’ve worked on, they had a bit of a missionary feel to them, but it’s not . . . it’s a bit more self-conscious. “We should do this.” It’s not as crazy. I mean, we were like religious zealots at Netscape. We were like, “Internet. The web. Browser. This is who we are. This is it.”

The other start-ups are not quite as insane, not quite so zealous-like about who they are. And sometimes, you know, they’ll make desks out of doors because some other start-up made desks. And Netscape was also very organic, as I said, because we didn’t really have any templates. So everything we did was just because, I don’t know, we didn’t know anything else! There were no other options. I mean there was no Internet then to Google everything for or do any research. So we were just kinda taking a stab at it.

And what I like about it, I think a lot of the choices that were made then were the right ones— like the Javascript, the CSS, and all that stuff. It’s a whole bunch of technology that’s still in use today. And even Mozilla still lives. We kind of felt like these were the things we were fighting for. We were just fighting for the technology, for what we believed in. SSL, too. I don’t know about the whole significant chain, but . . .

Brian: Do you have any particular memories of the IPO at all? I’ve heard from other guys that it wasn’t really that big a deal at the time. It was just a regular working day.

Aleks: It was not what that was all about. Not in the engineering. I think was a bigger deal in some other parts of the company. But the engineering, I think I slept through the IPO itself, because my usual work hours were till about 4 or 5 a.m. Then I would go back to sleep till, like, 10, then come into the office. So I just stumbled into the office as usual, and everybody was kind of hopping around saying, “Look, we went public, made some money. Great.” Talked it up, and then we went back to work.

But it was great. You know what? At the time, I didn’t appreciate it. Where the money really came in handy was after Netscape blew up. It’s like, “Well, everything blew up, but at least I got some cash to figure things out.”

Brian: So to that… You guys don’t get to bask in it too long before Microsoft starts to come after you. Was there a sense of competition between you guys and when Internet Explorer comes out, and you’re trying to compete feature-for-feature, and things like that?

Aleks: I don’t think that we got beaten on a feature-by-feature [basis]. I think because, yeah, the hard thing about the fight with Microsoft… it was not just the technical fight, right? They paid other people. My personal, humongous disappointment was: I’ve always been a Mac guy, although everybody laughed at me. The whole “Mac Daddy?” That was not a cool thing at Netscape. Everybody’s like, “Why are you working on that crappy little computer with no virtual memory?” I was the only one who had to worry about running out of memory because everybody else had virtual memory. No, not the Macs. So we had to write our own sockets libraries and all that. So Macs were not exactly popular hacker computers, but I love the Mac. I love the UI, all that stuff.

And then, when Mac . . . and I knew that Netscape was the best browser on the Mac. And then Apple decides to ship Internet Explorer with the Mac because Microsoft gave them a $100 million investment. That was kind of the stuff we were fighting. It was not purely technical.

So we kept up. And technically, we were pretty good, but the Microsoft guys have shipped software for the longest time, and I think they were developing three versions of the browser simultaneously. As opposed to us, we were working on one and really didn’t have the time for [inaudible 00:38:02]. So we made some technical mistakes here and there. But the fight was really lost in the Microsoft business assault cutting off our air supply. Making the price of the browser zero and even paying people to take their browser. And people were willing to pay us to ship ours, but they would say, “Look, not only will we give you ours for free, but we’ll actually give you money to ship ours.” So they cut off our air supply. So that’s how the fight was lost.

Brian: When I spoke to Lou Montulli, he said that for many years, he was bitter about that whole experience. Time has maybe healed things a bit, but did you feel the same way? Were you bitter about how things turned out vis-a-vis Microsoft?

Aleks: You know what I was really bitter about? Being sold to AOL. I mean, okay, Microsoft? A worthy opponent! Did they fight fair? No, they did not. But, you know, losing to Microsoft, I don’t mind. I mean, I do mind. I hate them. But it’s understandable. Now, being in a market where Netscape got sold to AOL? That was just depressing. I mean, that was the time I quit. I think my last day at Netscape was the AOL acquisition announcement. It was the saddest day.

Brian: Well, I don’t wanna wrap things up on that note. Let me dial back real quick and ask you about Marc Andreessen at Netscape. Did he . . .

Aleks: I can’t really tell you much of Marc at Netscape, because I rarely saw him.

Brian: That’s what Lou said, too.

Aleks: Yeah, Marc was already on a different level. He had moved away from coding into the executive suite. And Marc never looks back.

Brian: And what were your impressions of working with Jim Clark?

Aleks: Exactly. Well, Jim Clark was part of the executive suite. They were part of the executive suite.

We just all had dinner, our 20th anniversary dinner last week. I adore Jim Clark. I wish I got to work with him more. But I’ve never really worked closely with him.

So you want some nerd detail? Although he [Marc Andreessen] didn’t code, when he did code, he was awesome. One thing he did do in Mosaic that nobody ever appreciated, but it was really hard… There was this weird protocol called WAIS that is long gone. It was a purged protocol. Anyway, it was as ugly as LDAP is. Something people might be familiar with. Anyway, there was this one library in the world that actually spoke WAIS, because it was one of those things. You write it once, and you never wanna write that code again.

But it didn’t work. It was not inter-operable. And Marc, I think, spent, oh I don’t know, several weeks hacking on this horrible, horrible piece of code. Then he made the world’s first inter-operable WAIS library because he couldn’t stand it when he clicked a WAIS URL, you could not interrupt it if the server was down. So he had the programmer chops, back when he worked on Mosaic. Once we moved to Netscape, he never saw the code again.

Jim, on the other hand, I heard, always tries to code a little bit. When he did [inaudible 00:41:52] he tried putting some code in and stuff.

Brian: Right, right. That’s interesting.

Aleks: I mean, this is the stuff I’m thinking about these days. It might not be super interesting. But for me, I’m not used to being in a winning position. I come from a long tradition of geeks, where you’re just not . . . I mean, you’re not the winner. You’re the guys who’re really technical, and all that, but it’s really weird to see that the vision we had has just won over completely. And that revolution is still being played out. It’s gone . . . but 15 or maybe 10 years ago, it’s kind of gone beyond to what I could envision. And it’s still moving ahead full-steam. As Marc said, “Software eats the world.”

And another interesting thing is, when I . . . oh, I gotta tell you, this is the really funny part of the story. So when we came here, so we were six skinny geeky guys, and what we would do every once in a while to take a break from work was go to really fancy restaurants and eat. And the funny part is, every time we would show up at a fancy restaurant, they would put us at the worst table, because we were six geeky guys that didn’t look good, and, you know, wearing Kansas University shirts or something. And it’d be next to the bathroom.

Sometimes, I think, we went to Lulu’s, and they even when we walked in, they kind of looked at us, like, “Who are you people?” And then they would open up a whole new dining room and put us in there alone. And we used to call this “the Netscape table.” So every time we would go to the restaurant, it’d be like, “Hey, are we gonna get the Netscape table again?” It was always the one farthest away that nobody wants to look at. So that’s what it looked like in ’94.

And now it’s 2014, and the whole geek internet culture has completely taken over San Francisco. I mean, the start-up I’m working with right now, they’re on Maiden Lane, which is downtown Union Square where old San Francisco used to be, which is just crazy. So it has completely and utterly won. So of course now, as I said, I’m not used to be the winner. So I’m always like, “Oh, this can’t be good. People are in it for the wrong reasons. Why are they all acting so geeky and stuff?”

Brian: You don’t trust it.

Aleks: Exactly.

Brian: So to you, the thing that blows your mind 20 years on is that the geeks have taken over?

Aleks: Well, I don’t know if it’s true everywhere, but it’s definitely here in the valley. It seems to be that way. I mean, maybe I’m living in a bubble, but yeah. Our inside jokes are no longer geeky inside jokes. It’s just popular culture. Yeah. It’s crazy.

And you can go to the restaurants in your geeky outfits, and you’ll be treated well. And even the women don’t turn away from you. To me, it’s frankly mind-blowing. And now they’re even talking about the inclusion of women. I mean, I think it’s awesome that women are doing computer science. Where I come from, women wanted nothing to do with us, like… on a grand scale. We were just not interesting. So anyway, it’s just funny.

Brian: Well, so hopefully, the idea is there’s some 14-year-old coder out there listening right now, and she is . . . she’s gonna be happy that . . .

Aleks: Oh, I think it’s . . . I wish it was like this when I grew up. But as I said back then, women just . . . it was just not . . . not just women, but anybody sane would not go into that field.

Brian: Right. Well, right, that’s interesting. If you could look back at yourself when you were 25 and you’re doing all this stuff, could you do it now? If you had to go back and do it over again, could you do the hours? Could you do the intensity?

Aleks: You know, I’m actually a very serious family man right now. I mean, I have three kids. I adore them. It’s actually funny. Most of these early engineers at Netscape all ended up being these family guys that spend a lot of their time with the kids. Anyway, so for that reason, I would not do it right now. But ask me in two years when I’m done changing my last diaper. In a heartbeat.

Brian: With the right idea.

Aleks: Yes. I could have . . . I just loved it. It was really cool. It was a great feeling.

Brian: Well, Aleks, congratulations on 20 years.

Aleks: Thank you. I know. It makes me feel like a fossil.

Brian: No, no, hopefully not. If all this stuff is ancient history, then believe me, we’re all old at this point.

Aleks: Yeah.

Brian: Well, thank you for taking the time to talk to me.

Aleks: Well, thank you, you’re welcome. I enjoyed it. It’s funny. I don’t think about this stuff all that much. But you know, it’s funny, every time I do think about it seriously, it’ll raise the hair at the back of my neck.

Brian: Out of fondness, or . . .?

Aleks: No, it’s just . . . it was . . . I’m not religious, but that was the closest I’ve ever gotten to the religious feeling, almost. We were just one with the idea.

This interview totally made my Monday morning! Aleks tells it like it is in a humorous and real way.

Thank you!!

I know I seem impatient, but when is the next episode?

I’ve got a few more interviews scheduled for this week for the 20th Anniv. of Netscape next month. Will start recording next “chapter” this week as well. Topic: early online services, Prodigy, CompuServe, AOL, etc…

[…] Chapter 1, Supplemental 3 – An Interview With Aleks Totic […]