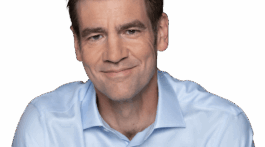

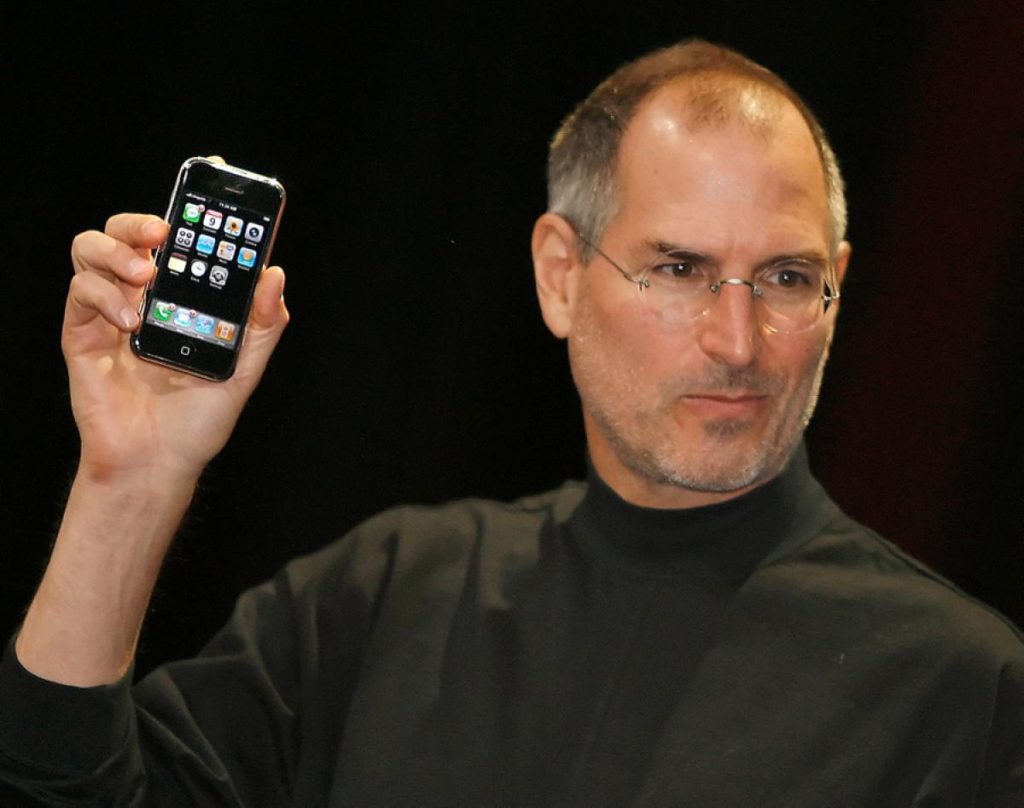

Those words have become so famous in the history of technology that I imagine a large percentage of readers have them memorized. Ten years ago this Monday, January 9, Steve Jobs stood on stage and announced the iPhone to the world. It was the crowning achievement in the career of the greatest technologist of our time, the moment that the modern era of computing began.So… Three things: A widescreen iPod with touch controls. A revolutionary mobile phone. And a breakthrough internet communications device. An iPod… a phone… and an internet communicator… An iPod, a phone… are you getting it? These are not three separate devices. This is one device! And we are calling it iPhone.”

- Steve Jobs, January 9, 2007

On the ten year anniversary of the birth of the iPhone, this is the story of that moment and the history of that device which can take a rightful place alongside the original Macintosh, the first IBM PC, the Apple I, the Altair 8800, the DEC PDP-8, the IBM System/360 and the ENIAC as one of most important machines to have brought computing into everyday life.

What follows is a lightly edited transcript of an Internet History Podcast special episode marking the 10th Anniversary of the iPhone. You can listen to the full episode here:

And if you enjoy what you hear, please consider subscribing to the podcast for more than 125 episodes of Internet History just like this.

Keep reading below…

The Roots of the iPhone

At the beginning of 2007, Apple was a company on a winning streak. Its flagship Mac line of computers was growing in market share at the expense of traditional PCs. The iPod, introduced a little over five years earlier, had transformed Apple from a niche company that made high-end personal computers into a company that made the most sought-after gadgets in the world. And yet, despite this success, few (outside the company, at least) would have been brave enough to predict that Apple was about to release the gadget-to-end-all-gadgets—the most transformative (and most personal) computer of the modern era.Apple was famously (or, infamously) one of the pioneers in handheld computing. The Newton MessagePad was the first PDA (a term Apple coined) to generate broad mainstream appeal when it was released in 1993. The Newton had many details that eerily echoed what would come later: the device measured 4.5″ x 7″, had a touchscreen in lieu of a keyboard, was priced at $699 (about $1129 when adjusted for inflation), sported a 32-bit ARM CPU and it even had a Siri-like feature called the Newton Assistant.

But this was 1993. The web had not yet gone mainstream. There was no such thing as ubiquitous cellular data networks or wifi hotspots. And crucially, multi-touch technology was not available. Users interacted with the touchscreen via a stylus, not their fingertips, and input information via text-based handwriting recognition software. Problem was, the handwriting recognition wasn’t all it was cracked up to be, as the comic strip Doonesbury and the tv show the Simpsons lampooned endlessly. The Newton became a joke and sold less than 50,000 units in its first four months. A few years later, when Steve Jobs returned to Apple and famously streamlined the company’s bloated product line, the Newton was discontinued. But in the meantime, it had pioneered the PDA market that Palm and others would exploit to great success in the later 90s, and would set the functional template for smartphones in the 2000s.

This experience beyond traditional computers, disastrous as it may have been for the company, nonetheless planted some residual ideas within Apple’s corporate DNA. And after Jobs returned to save the company from extinction, memories of pocket-sized devices resurfaced to take Apple into a new era. The iMac might have been the product that saved Apple as a company, but the iPod was the product that transformed it. Released in 2001, the iPod reached beyond Apple loyalists and became a bonafide mainstream sensation. Eventually, the iPod was responsible for 45% of Apple’s total revenue. It also captured 70 percent of the MP3 player market.

This is something that has been a bit glossed over in recent histories of the company, but stop for a minute and imagine how momentous a change the iPod engendered within Apple itself. This was a company that, for nearly 30 years, had been a personal computer company. The blue sky thinking that allowed Apple to make a stand-alone MP3 player—to enter a mature market as an outsider and believe it could dominate—also engendered the sort of fearlessness that made it possible to break with other long-standing Apple shibboleths. The iPod eventually worked with Windows machines, even at the risk of cannibalizing Mac sales. iTunes eventually worked with Windows machines. Apple (gasp) made a Windows app! As Phil Schiller told Walter Isaacson in his Steve Jobs biography: “We felt we should be in the music player business, not just in the Mac business.” It was this conceptual leap, this strategic bravery (just as much as a penchant for good design and reliable manufacturing) that would be responsible for Apple’s success in the 2000s.

Apple was no longer just a computer company. It could be whatever it wanted to be.

No longer just a computer company… Apple was suddenly a consumer electronics juggernaut. Like the Sony Walkman before it, the iPod put a trendsetting device into everyone’s pocket. Jobs had long admired the power that Sony had wielded over the electronics and media industries in the 1970s and 80s, and almost overnight, Apple enjoyed a similar measure of power. This industrial muscle was proven conclusively when Jobs corralled the major music companies into the iTunes store. The leverage of a dominant product like the iPod had allowed Apple to transform (some said, take over) an entire ancillary industry. Flush with this success, the brain trust at Apple began to wonder what other industries they might be able to disrupt. According to Phil Schiller, the iPod, “really changed everybody’s view of Apple both inside and outside the company.” Apple began to wonder if it might be able to apply its secret sauce of product development and design to other industries. They considered making Apple cameras, and even (at this early date) an Apple car. “Crazy stuff,” Schiller would remember.

In many ways, this blue-sky mentality caused history to repeat itself. Back in the 80s, the fathers of the Newton had been motivated by a desire to anticipate the next evolutionary step in computing. Steve Sakomen, Jean-Louis Gassee and then-Apple CEO John Sculley imagined a world beyond keyboards and mice—in short, a world of hand-held computing. 15 years later, the new (and returned) Apple leadership found itself imagining a similar future.

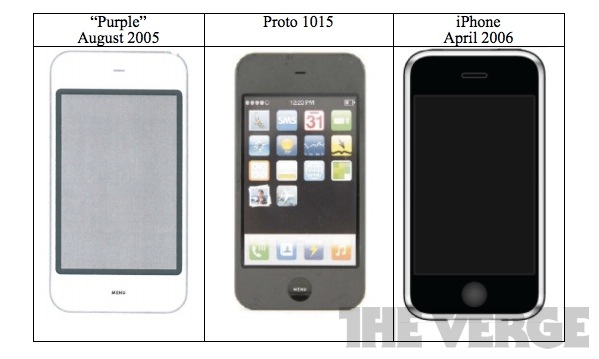

“In 2003, we had built all these great Macs and laptops and we started asking ourselves what comes next,” remembered Scott Forstall. “One thought we settled on was a tablet. We settled pretty quickly if we could investigate doing that with a touchscreen, so we started investigating and building prototypes.”

At the same time, Steve Jobs had an eye not just on the future of computing, but on the future of the iPod. By the mid-2000s, it wasn’t just MP3 players that were bulging people’s pockets; cellphones were reaching ubiquity as well. “He [Jobs] was always obsessing about what could mess us up,” Apple board member Art Levinson told Walter Isaacson. Apparently, Jobs decided that: “The device that can eat our lunch is the cell phone.” It was clear to everyone that consumers would prefer one, single, converged device, as opposed to carrying around several. As he was never one to milk a cash cow into oblivion, Jobs was eager to create some version of an iPod/phone before a competitor beat him to it… even if that meant making the iPod obsolete.

According to Tony Fadell, Apple was thinking: “‘How do we make sure that we are at least competitive so that anyone who is carrying a cell phone can get iTunes music?’ Because if we lost iTunes, we would have lost the whole formula.”

As Jobs told Walt Mossberg at the 2010 All Things D conference: “I had this idea about having a glass display [tablet], a multi-touch display you could type on. I asked our people about it. And six months later they came back with this amazing display. And I gave it to one of our really brilliant UI guys. He then got inertial scrolling working and some other things, and I thought, ‘my god, we can build a phone with this’ and we put the tablet aside, and we went to work on the phone.”

And so, a skunkworks tablet project became a skunkworks phone project. At the very least, by 2003-4, in the form of various initiatives, Apple was hard at work on some sort of portable device that would merge the iPod with a phone and become an all-encompassing unitary device.

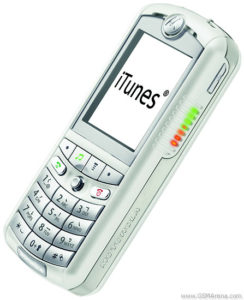

The Rokr Dead End

As many commentators and historians have noted, it was not like Steve Jobs said, “Let there be iPhone” and the conceptual became real. Instead, the development process that led to January 9, 2007, was convoluted, encompassing several different initiatives (as many as five separate projects, according to some accounts) before the competing ideas and prototypes fell by the wayside and the final solution was settled upon.Initially, the idea was fairly simple: add phone functionality to an iPod, and/or add iTunes software to existing phones.

“There was all kinds of different gestations of it,” Tony Fadell would recall on On the Verge. “There was an iPod, plus phone… and then there was the iPhone… and then there was the next generation iPhone… and that’s the one that actually shipped.”

As many online speculators guessed, early prototypes delivered by Fadell’s iPod team featured an iPod-like device with added-on communication features. The problem was that the vaunted click-wheel, while a brilliant UI hack when selecting songs from a list of albums, was not exactly ideal for dialing a phone—much less inputting things like text messages. “We were having a lot of problems using the wheel, especially in getting it to dial phone numbers,” Fadell told Isaacson in his Steve Jobs biography. As Fadell told Josh Topolsky: “The biggest problem with the iPod, plus phone, was that we had a little screen and we had this hardware wheel and we were stuck with that.”

A second prototype focused more on being a video player, or, what at the time was called a PMP, a Portable Media Player. The problem in this case was delivery of media. In those pre-3G wireless days, the bandwidth simply wasn’t available to accommodate video. At the same time, Apple’s internal Airport wireless team was tasked with investigating cellular technology. This turned out to be a dead end because, of course, cellular technology is drastically different than wifi.

And so, the decision was made to reach out to existing phone manufacturers to see what Apple could learn. The idea of purchasing Motorola outright was briefly considered in 2003, a notion that made synergistic sense since Apple had a long history with the company. Through the 90s, Motorola supplied the CPUs for Apple’s portfolio of Macs. What was more, in the early 2000s, Motorola had a hit lineup of cellphones in the form of the Razr. So Apple could partner with a company that knew how to design slick, thin, sexy handsets.

“We looked around the industry, and in early 2004 we settled on working with Motorola, which at the time completely dominated the handset business with its RAZR flip phone.” Eddy Cue told Brent Schlender and Rick Tetzeli in the book Becoming Steve Jobs. “Everybody had one [a RAZR].”

But the main motivation for Apple’s eventual dalliance with Motorola came from Apple’s acute reluctance to do business with the major cell carriers. At the time, cellular hardware was almost an afterthought in the mobile industry; handsets were virtually feature-indistinguishable, often offered free on-contract in order to sign users up to expensive long-term contracts. The carriers dictated what the phones could do, even how they could look. These were not compromises Apple would ever be willing to make for a device it put its name on. “We’ve visited with the handset manufacturers and even talked to the Treo guys,” Jobs said at the D conference in 2004. “They tell us horror stories [about working with the carriers].”

So working with Motorola seemed to offer something of a compromise solution. Apple would merely license iTunes software, Motorola would design the hardware, and—most importantly—it would also deal with the carriers. “We thought that if consumers chose to get a music phone instead of an iPod,” remembered Tony Fadell, “At least they would be using iTunes.”

Apple probably thought it was putting iTunes on the sleek and sexy Razr. Instead, it ended up with the clunky Rokr. Motorola took 18 months to deliver the candy-bar style device and it was fatally, almost ridiculously, limited. The Rokr could only hold one hundred songs, a restriction the Motorola engineers arrived at seemingly randomly since the storage capacity allowed for much more. And even though the device boasted internet access, iTunes purchases could not be made over the air. You had to plug your phone into your computer to load it with music. When Jobs unveiled the Rokr in September 2005, he could barely hide his contempt. Whether subconsciously or passive aggressively, Jobs even fumbled the demo of the Rokr, something that did not typically happen in a Steve Jobs presentation.

“Well… I’m supposed to be able to resume the music right back to where it was,” he said onstage during the announcement. “Oops! I hit the wrong button!”

According to the book Digital Wars: Apple, Google, Microsoft and the Battle for the Internet by Charles Arthur, within a month of going on sale, customers were returning the ROKR at six times the industry average for a new device.

Wired magazine famously asked of the Rokr, “You Call This the Phone of the Future?”

The Rokr was a puzzling detour for Apple, a company that famously likes to control the entire user experience from hardware to software. This dead-end can only be explained by Jobs’ continued reluctance to deal with the cellular carriers firsthand. “We’re not the greatest at selling to the Fortune 500, and there are five hundred of them!” Jobs said at the 2003 All Things D conference. “In the cell phone business, there are five. We don’t even like dealing with five hundred companies! (…) You can imagine what we thought about dealing with five.”

Jobs’ disgust was so pronounced, Apple began seriously considering jumping into the MVNO business, buying wireless bandwidth wholesale and selling cellular service under its own brand. This would have cut the carriers out of the equation entirely and allow Apple to control the entire experience. At the time, Apple was rapidly expanding its retail store footprint, so it theoretically could have managed a nationwide sales and service rollout. It could build a phone that would function on its own network and it wouldn’t have to go begging to the carriers simply for the privilege of adding features and services.

It was during this exploration of an “Apple Wireless” idea that the final pieces of the iPhone we know and love fell into place.

Blame The Carrier

The star-crossed Rokr had been developed in partnership with the wireless carrier Cingular (soon to become AT&T after a series of mergers). At the time, Cingular was struggling to compete with industry leader Verizon. And this was just at the precise moment that 3G cellular service was beginning to roll out nationwide. 3G was designed to deliver wireless data at near broadband speeds. The cell carriers knew that data was the growth product of the future, but—hard as this is to imagine in 2017, when making calls is almost an afterthought when it comes to how we use our devices on an everyday basis—they were having a hard time getting consumers to sign up to get internet on their cellphones.While the Rokr was being developed, Cingular executives tried to convince Jobs to drop his MVNO plans and instead create an Apple phone exclusively for their network. Cingular’s motives were mostly defensive. The carrier feared that if Apple launched a competing carrier service, they would under-price wireless plans in order to encourage hardware sales. This would commoditize data-plans before they even had a chance to catch on. At first, Jobs refused even to listen to Cingular’s entreaties. But the disaster of the Rokr began to change his thinking.

“Jobs hated the idea of a deal with us at first,” Cingular executive Jim Ryan said in the book Dogfight, by Fred Vogelstein. “Hated it. He was thinking he didn’t want a carrier like us anywhere near his brand. What he hadn’t thought through was the reality of just how damn hard it is to deliver mobile service.”

Indeed, the customer service, logistical, technical and reliability issues of operating a nationwide cellular network were something Apple had zero experience with. Ryan emphasized these potential headaches to Jobs. “Funny as it sounds, that was one of our big selling points to [Apple],” Ryan recounted in Dogfight. “Every time the phone drops a call, you blame the carrier. Every time something good happens, you thank Apple.”

At the same time Cingular was trying to sell Jobs on the idea of making an Apple phone internally, a handful of Apple execs, especially Mike Bell and Steve Sakoman, were making the same argument within the company.

“I argued with Steve for a couple of months and finally sent him an email on November seventh, 2004,” Bell says in Dogfight. “I said, ‘Steve, I know you don’t want to do a phone, but here’s why we should it: [Jony Ive] has some really cool designs for the future iPods that no one has seen. We ought to take one of those, put some Apple software around it, and make a phone out of it ourselves instead of putting our stuff on other people’s phones.’ He calls me back about an hour later and we talk for two hours, and he finally says, ‘Okay, I think we should just do it.'”

Apple ended up dealing with AT&T because AT&T was eager for a differentiator. “We actually knew Verizon better than we knew AT&T,” Eddie Cue says in Becoming Steve Jobs. Cue was the one tasked with negotiating with the carriers. “[Verizon] thought cellular was their playground. Sort of like, ‘You’re gonna play our game by our rules.’ (…) When we went to see [AT&T] (…) we really liked them. You could tell they were hungrier and wanted to show what they were capable of.”

The deal Apple would cut with Cingular/AT&T would take a year to finalize, but it alleviated almost all of Jobs’ concerns. In exchange for an exclusive right to an Apple phone on their network, AT&T would grant Jobs carte-blanche to design the phone as Apple saw fit. It would be completely Apple-branded and AT&T would have no say in the features or services the phone offered. As icing on the cake, Apple would get a share of the monthly cellular data payments users would have to cough up to use with the device.

An Apple phone would finally be a reality. And that was where the difficulty really began.

Jobs Was Not Impressed

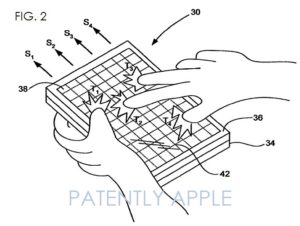

According to various accounts, Apple produced at least three—but possibly as many as six—prototypes of a phone. Again, the earliest iterations grew out of the company’s experience producing iPods. But one idea, the back-burnered tablet project, kept coming to the fore.“The story was that Steve wanted a device that he could use to read e-mail while on the toilet — that was the extent of the product spec,” Joshua Strickon, an Apple engineer says in Dogfight. Jobs wanted a simple slate and wanted interaction to be done via touch input. The problem was, capacitive multi-touch had never been done on a consumer device before, much less on a device small enough to function as a phone.

Part of this problem was solved by the acquisition of a company called Fingerworks, which had moved capacitive technology forward quite considerably. And multi-touch was championed by an Apple engineer named Greg Christie, who had worked on the Newton all those years ago. He knew that multitouch would allow for the entire device to basically be a screen, empowering the software to make up for hardware deficiencies. A keyboard could spring up only when the user needed it. Photos could be manipulated and displayed at full brilliance. Apple could get closer to Fadell’s video-player device, and now that it was partnering with a carrier committed to rolling out 3G spectrum, the problems of bandwidth would soon not be an issue. And web browsing could be made to approximate a desktop experience.

Over the course of 2004, Christie worked with another engineer named Bas Ording to create a demo that showcased what multi-touch was capable of. Jony Ive described their prototype system as the “Jumbotron” because it projected a videoscreen on a touch-sensitive surface the size of a table. Ive was especially impressed with the demo and arranged to show it to Jobs.

But Jobs was not impressed.

“He was completely underwhelmed,” Ive says in Dogfight. “He didn’t see that there was any value to the idea. And I felt really stupid because I had perceived it as a very big thing.”

But then, as often happened over Jobs’ long career, an idea that he initially rejected as brain-dead grew on him until he began to champion it as a solution himself.

By mid-2005, Jobs was evangelizing the touch-features we’re familiar with today, things like pinch-to-zoom and inertial scrolling. “He said, ‘Tony, come over here. Here’s something we’re working on. What do you think? Do you think we could make a phone out of this?'” Fadell recalled.

Hard as it may be to believe in retrospect, at that point, there were still people inside Apple who remained wedded to the idea of a physical QWERTY keyboard with hardware keys. “It was definitely discussed,” Fadell would remember later. “It was a heated topic.”

But one by one, people were won over by the possibilities touch made possible. In the Apple-Samsung trial, Scott Forstall testified: “I’ll never forget we took that tablet and built a small scrolling list. On the tablet, we were doing pinch and zoom. So we built a small list to scroll on contacts and then you could tap on it to call. We realized that a touchscreen that was the size that would fit in your pocket would be perfect for the phone.”

Fadell remained skeptical that it could all be made to work. “I wanted it to work because it made sense that you wanted a full screen. You didn’t just want a little keyboard,” he would say later. But there were any number of practical and manufacturing roadblocks to consider. “You had to go to LCD vendors who knew how to embed technology like this in glass; you had to find time on their line; and then you had to come up with compensation and calibrating algorithms to keep the pixel electronics from generating all kinds of noise in the touch-screen. It was a whole project just to make the touch-screen device. We tried two or three ways of actually making the touch-screen until we could make one in enough volume that would work.”

But Jobs had been won over. “You’ve figured out how to blend music and a phone,” Becoming Steve Jobs reports Jobs telling Fadell. “Now go figure out how to add this multi-touch interface to the screen of a phone. A really cool, really small, really thin phone.”

Project Purple

The project was codenamed “Project Purple.” But even as the goal was finalized, the nature of the end product was up in the air until the very last minute.“I was actually pushing to do two sizes—to have a regular iPhone and an iPhone mini like we had with the iPod,” Apple’s chief hardware executive Jon Rubenstein says in Dogfight. “I thought one could be a smartphone and one could be a dumber phone. But we never got a lot of traction on the small one, and in order to do one of these projects you really need to put all your wood behind one arrow.”

Jobs wanted the phone to run on a modified version of OS X, but fitting that much code onto a phone chip proved difficult. So Forstall was tasked with putting OS X on a severe diet, while Fadell was, essentially, told to expand the iPod OS. Forstall’s team ended up winning the software bakeoff and the end result, iOS, would eventually be a tenth of the size of OS X while still sharing plenty of the desktop OS’s traits.

With Jobs’ famous obsession with secrecy, Forstall was told he couldn’t hire anyone from outside the company to work on his part of the project; but he was nonetheless free to pick liberally from internal talent. Forstall didn’t tell recruits what, exactly, they would be working on. He only divulged that they would be expected to, “give up untold nights and weekends and that you will work harder than you have ever worked in your life.”

As eventually became standard practice at Apple, the phone team was segregated even from other Apple employees. “The team took one of Apple’s Cupertino buildings and locked it down,” Forstall would recall in later court testimony. “It started with a single floor with badge readers and cameras. In some cases, even workers on the team would have to show their badges five or six times.”

The floor became known as the “purple dorm.”

“We put a sign on over the front door of the iPhone building that said FIGHT CLUB,” Forstall testified. “Because the first rule of fight club is that you don’t talk about fight club.”

“When creating the iPhone, there were so many completely unsolved problems that we had to tackle,” Forstall said. “Every single part of the design had to be rethought for touch.” On a screen so small, allowances had to be made for imprecise gestures. And on a device with only a single pane for input, innovations like slide to unlock had to be invented just to make it functional in a new user paradigm.

One of the biggest software problems was the virtual keyboard. It was one thing to implement gestures and swipes and pinch-to-zoom on a 3.5-inch screen. It was another thing entirely to type on a tiny keyboard that made up only about 1/3rd of that real estate. “Everyone was concerned about touching on something that doesn’t have any physical feedback,” an anonymous Apple executive recounts in Dogfight, saying that perfecting the keyboard was a “make-or-break kind of thing,” for the device.

There were plenty of issues to tweak across the whole spectrum of the software. If you tried to type the letter “e” it tended to trigger a range of other letters instead. And there was a significant lag between a virtual keystroke and a given letter actually appearing on screen. But solving software problems can sometimes trigger software inventions as well. Forstall himself came up with the idea of the double tap to zoom in on text. “The team went back and worked really hard to figure out how to do that,” Forstall said later.

But if getting the software to work was a challenge, the hardware was even more so. It didn’t help that the engineers working on the hardware were forbidden from seeing the software that they were ostensibly designing for. But the biggest issue was that Apple simply hadn’t dealt with the basic realities of cellphone design before. The team had to take a crash course in basic physics. About a dozen radio-frequency simulators were purchased. To determine the radiation the new devices were spitting out, engineers built models of the human head to test against.

Apple also had no experience with the rigorous testing required to a) function on AT&T’s network and b) pass FCC muster. Handset manufactures usually left this process to the carriers to sort out, since they were the ones that knew their networks the best. But, again, Apple was keeping AT&T at arms-length. And so the team instigated an intensive dogfooding protocol among Apple employees. “It wasn’t ‘Carry an iPhone—and a Treo,” an Apple engineer said, “It was ‘Carry an iPhone and live on it.'”

This was coupled with a signal testing regimen that was nothing if not ad-hoc. Often, testing was nothing more than driving the phones around in cars and finding dead spots and diagnosing dropped calls on the spot. “Sometimes it would be ‘Scott [Forstall] had a call drop. Go figure out what’s going on,'” an engineer named Shuvo Chatterjee remembered when describing the process in Dogfight. “So we’d drive by his house and try to figure out if there was a dead zone. That happened with Steve too. There were a couple of times where we drove around their houses enough that we worried that neighbors would call the police.”

One intermediate prototype that was championed by Jobs and Ive was based off of an unreleased iPod design that Ive had developed previously. The device was made of brushed “aluminium,” of course. But in this case, the master aesthetes had to bow to the laws of nature. “I and Ruben Caballero [an antenna expert] had to go up to the boardroom and explain to Steve and Ive that you cannot put radio waves through metal,” Apple engineer Phil Kearney said in Dogfight. “And it was not an easy explanation. Most of the designers are artists. The last science class they took was in eighth grade. But they have a lot of power at Apple. So they asked, ‘Why can’t we just make a little seam for the radio waves to escape through?’ And you have to explain to them why you just can’t.”

In other famous cases, Jobs’ exacting demands won out, to the eventual benefit of the final product. The screen of the phone was originally supposed to be composed of the same plastic that iPod screens were made of. But after a day in Jobs’ pocket, the prototype unit suffered from deep and permanent scratches thanks to his car keys. On a dime, Jobs switched the screen from plastic to Gorilla glass, even talking Corning into converting an entire factory in Harrisburg, Kentucky to produce the quantities Apple needed. This actually complicated things for the hardware team, since the multitouch sensors now had to be embedded in glass, and glass was an entirely different proposition from embedding in plastic.

“This is a day I’ve been looking forward to for two and a half years.”

The iPhone was announced a full six months before it eventually went on sale. At the time of the unveiling, the device was nowhere near ready to be shown to the public. There were only about a hundred iPhones that even existed, all in various stages of prototype. The software was still in a transitional phase, and the phone’s cell radio didn’t communicate reliably with the processor. The radio problem was so desperate that Apple briefly dropped its secrecy obsession and flew in engineers from Samsung (the processor) and Infineon (the cell radio) in order to figure things out.Demoing a half-baked product was not how Steve Jobs was used to doing things, but his hand was forced. For one thing, the fact that an Apple phone was coming was common knowledge by this point. Reviewers, bloggers and reporters had whipped up an incredible frenzy of excitement over what they dubbed the “Jesus Phone.” Another consideration was the fact that early January was the annual Macworld event and Jobs had given the keynote at every Macworld since he had returned to Apple in 1997. If Jobs took the stage and only announced availability of the new (and experimental) Apple TV, people would have known something had gone wrong with the Jesus Phone. Finally, there were serious contractual concerns. AT&T had been left mostly in the dark over the course of the iPhone’s developmental process. They had only seen one of the prototypes a few weeks previously.

If the iPhone didn’t launch that week, AT&T could potentially back out of the entire deal.

Apple took over the Moscone Center in San Fransisco to host of the launch event. A lone Apple employee was tasked with driving all 24 of the demo units in the trunk of his Acura and delivering them to San Francisco. He was followed by a second car piloted by Apple security. The engineer wondered what would happen if he got into an accident and the demos were destroyed.

Jobs himself approved the list of people who could participate in the preparations, and more than a dozen security guards were on post 24 hours a day. Jobs originally decreed that all outside contractors hired to staff the event would have to sleep in the building the night before so that no details could leak out. Cooler heads eventually talked him out of it.

Jobs rehearsed his presentation for six solid days, but at the final hour, the team still couldn’t get the phone to behave through an entire run through. Sometimes it lost internet connection. Sometimes the calls wouldn’t go through. Sometimes the phone just shut down.”It quickly got very uncomfortable,” Andy Grignon, the senior radio engineer for the iPhone remembered in Dogfight. “Very rarely did I see him become completely unglued. It happened. But mostly he just looked at you and very directly said in a very loud and stern voice, ‘You are fucking up my company,’ or, ‘If we fail, it will be because of you.'”

Those scenes from the Jobs biopic didn’t just come from Aaron Sorkin’s imagination.

The engineers identified a “golden path,” a specific set of demo actions that Jobs could perform in a specific order that afforded them the best chance of the phone making it through the presentation without a glitch. For example, Jobs could send an email and then surf the web, but if he reversed the order, the phone tended to crash.

Grignon and the other engineers masked the wifi that Jobs would be using onstage so that audience members couldn’t jump on the same signal. AT&T brought in a portable cell tower to make sure Jobs would have a strong signal when he made his demo phone call. But, just to be on the safe side, the engineers hard coded all the demo units to display five bars of cell strength, whether that happened to be true or not.

One more motivation for going through with the announcement come hell or high water was the fact that the annual Consumer Electronics Show was taking place at the exact same time. Jobs intended to steal attention and headlines from whatever was being announced in Las Vegas. Sure enough, on January 6, an army of reporters, bloggers, journalists and critics dutifully boarded planes at McCarran airport and flew back to San Francisco.

In the audience that Tuesday were Andy Hertzfeld, Bill Atkinson and Steve Wozniak. Just as with the iMac launch, Jobs made sure the original Macintosh team was present to bear witness to history being made.

“iPhone was the culmination of everything for Steve, and of everything I had learned,” Eddy Cue says in Becoming Steve Jobs. “It was the only event I took my wife and kids to because, as I told them, ‘In your lifetime, this might be the biggest thing ever.’ Because you could feel it. You just knew that this was huge.”

Somehow, the iPhone launch went on without a hiccup. Watching the video, Jobs is masterful, at the very height of his powers as a showman. You can feel him simultaneously stoking and feeding off of the energy from the crowd. It is almost as if Jobs can’t believe what he is demoing at the same time the audience can’t believe what they’re seeing.

The team that had put the demo together celebrated by getting wasted.

“It was the best demo any of us had ever seen,” the antenna engineer Grignon recalled. “And the rest of the day turned out to be just a shit show for the entire iPhone team. We just spent the entire rest of the day drinking in the city. It was just a mess, but it was great.”

Baby Steps

The original iPhone was based on the Purple 2 prototype, code named M68, with device number iPhone1,1. It had a 3.5-inch LCD screen at 320×480 and 163ppi, a quad-band 2G EDGE data radio, 802.11b.g Wi-Fi, Bluetooth 2.0 EDR, and a 2 megapixel camera. It had an ARM-based 1176JZ(F)-S processor and PowerVR MBX Lite 3D graphics chip. It had a 1400 mAh battery and came with 128MB of RAM. Storage came in two flavors: 4GB or 8GB NAND Flash. It had an accelerometer for screen rotation, a proximity sensor for detecting when the phone was up against your face, and an ambient light sensor for screen brightness. The pin connector was the same one used on the iPod, allowing for connection to iTunes and charging. The standout feature on the day of the announcement was one that most of us could care less about today: visual voicemail.But there were omissions as well: It had no GPS. You couldn’t remove the battery. You couldn’t add additional storage. It took photos, but no video.

A decade on, there are three especially glaring downsides to the original iPhone.

The first was the price. The two versions of the phone retailed at $499 for the 4GB and $599 for the 8GB model. On-contract. There was no carrier subsidy. Before or since, Apple and its apologists have been loathe to admit that this was a mistake. In the first quarter, the iPhone was on sale, it sold 1.5 million units. But there is no telling how many more could have sold had the price been in line with other phones on the market. A mere months after the phone went on sale, the AT&T contract was renegotiated. Now, AT&T would buy the iPhone directly from Apple, and consumers would receive a subsidy that would bring the price more in line with industry standards.

Second, even though the iPhone introduced the promise of a cell phone that could deliver a genuine web browsing experience, it was still on the second generation EDGE network. AT&T was still in the process of building out its 3G network, so for that first generation phone, users had to make due with snail-like speeds. A big reason for this was the fact that 3G chips were not available at the time development of the phone had begun. But the fact is, this was also a purposeful hedge made by AT&T and Apple. They knew they weren’t ready for the amount of bandwidth iPhone users would soon be hoovering up. The decision to stick with EDGE was a decision to play for time. If anything, the iPhone was launched onto AT&T’s network about 18 months too early. The network couldn’t handle the surge in data usage, as early iPhone users could grumblingly attest to, but these early adopters were intended to be sacrificial lambs until the infrastructure could catch up.

But most importantly, people tend to forget that the iPhone launched without the app store. Most of us are now used to using our phones as a sort of utility belt of tools, with apps allowing us to do any number of things that stand-alone devices used to be required for. The original iPhone lacked the second, truly revolutionary innovation that would kickstart the smartphone era: apps.

The original, App Store-less iPhone was very much Steve Jobs’ platonic ideal of a closed and curated system. And for a long time, Jobs stuck to his guns, refusing to let outside developers work with the iPhone.

“The full Safari engine is inside of iPhone. And so, you can write amazing Web 2.0 and Ajax apps that look exactly and behave exactly like apps on the iPhone,” Jobs told developers in 2007. “And guess what? There’s no SDK that you need! You’ve got everything you need if you know how to write apps using the most modern web standards to write amazing apps for the iPhone today. So, developers, we think we’ve got a very sweet story for you. You can begin building your iPhone apps today.”

Later, he told John Markoff of the New York Times: “You don’t want your phone to be like a PC. The last thing you want is to have loaded three apps on your phone and then you go to make a call and it doesn’t work anymore. These are more like iPods than they are like computers.”

But, again, key executives inside Apple badgered Jobs until he changed his mind. In Becoming Steve Jobs, Eddy Cue remembers Jobs’ capitulation on the subject of third party apps: “Oh, hell, just go for it and leave me alone!”

Within months, Jobs would be singing the praises of the app store. As with the notion of multi-touch, once Jobs came around, he could become an idea’s biggest cheerleader.

With the 2nd iPhone, the iPhone 3G, all of these problems would be solved: it retailed for $199 for the 8GB model and $299 for the 16GB model; it had 3G wireless speeds; it had the App Store. “It was only then that the iPhone was truly finished,” Jean-Louis Gassee has said. “That it had all its basics, all its organs. It needed to grow, to muscle up, but it was complete as a child is complete.”

“Every Once in a While, A Revolutionary Product Comes Along that Changes Everything”

At the time of this writing, more than 1 billion iPhones have been sold.But numbers can’t tell the whole story of the iPhone’s impact on the world. Perhaps, in cases like this, anecdotal examples can be unusually illustrative. If I had told you in 2007 that your mother would one day carry a smartphone and use it on an hourly basis, would you have believed me? Would Facebook be at a billion users today if the iPhone hadn’t presented the perfect vehicle for social media consumption and production? And if not for the iPhone kickstarting the smartphone revolution, whither Snapchat? Or Twitter? Much less, Uber? If not for the iPhone, I would posit that the mobile revolution would have kicked off at least 5 years later.

With ten years of perspective, perhaps the most remarkable thing about the iPhone is the fact that, for all its retrospective imperfections, the original model was in fact so conceptually perfect, right out of the gate. Automobiles had to evolve for almost 40 years until they settled into the standard configuration we are familiar with today. On their first attempt, the team at Apple managed to stumble upon the perfect form factor, the perfect incarnation of the modern smartphone. Smartphones had existed for several years previous to the iPhone, but the standard form of the smartphone as we know it today—physical keyboard-less, a single slab of screen, a “black mirror” that is both a reflection of, and a conduit for, all of our hopes and desires—they nailed it on the first try. And that’s quite remarkable. Whatever you may think about the subsequent lawsuits and charges of copycat-ing, there’s a very good reason why everyone in the industry moved toward the paradigm the iPhone pioneered.

The bottom line is, the first iPhone marks a clear delineation in technological eras. It’s not just that nearly every adult in the developed world now has a smartphone in their pocket… it’s that nearly every adult in the developed world now has a computer in their pocket. If you look at the overall penetration of daily computer users, before the smartphone era, a large percentage of humanity did not use computers on a daily basis, especially in the developing world. The smartphone is rapidly allowing every adult human access to computing on a daily basis.

For more than thirty years of the PC era, visionaries dreamed of empowering humans with computers. The guys at the Homebrew Computer Club imagined a day when everybody had personal access to their own computer. Microsoft’s motto was, famously, “A computer on every desk and in every home.” The dream of ubiquitous computing is finally, rapidly coming to pass. And that is because of the smartphone. And the iPhone was the first smartphone to make smartphones matter.

In 1960, a computer visionary named JCR Licklider published one of the seminal papers in the history of computer science, entitled “Man-Computer Symbiosis.” In it, he argued that while artificial intelligence and sentient computers were probably inevitable in the long run, in the short term, there would probably be an extended period of time where humans and computers would co-exist symbiotically:

In short, it seems worthwhile to avoid argument with (other) enthusiasts for artificial intelligence by conceding dominance in the distant future of cerebration to machines alone. There will nevertheless be a fairly long interim during which the main intellectual advances will be made by men and computers working together in intimate association. The hope is that, in not too many years, human brains and computing machines will be coupled together very tightly and that the resulting partnership will think as no human brain has ever thought and process data in a way not approached by the information-handling machines we know today.

Today, we use our smartphone to navigate nearly every minute of our modern lives. Every time you see someone, head down, engrossed in their phone, it’s worth realizing that the truly personal computer revolution came in the form of a phone. Of course, it isn’t just a phone, it’s a tiny supercomputer. And so, the man-computer symbiosis that Licklider imagined all those years ago has come to pass.

That is the ultimate legacy of the first iPhone.

Bibliography/Sources:

- Dogfight: How Apple and Google Went to War and Started a Revolution, by Fred Vogelstein

- Becoming Steve Jobs: The Evolution of a Reckless Upstart into a Visionary Leader, by Brent Schlender and Rick Tetzeli

- Digital Wars: Apple, Google, Microsoft and the Battle for the Internet

- Steve Jobs, by Walter Isaacson

- https://www.wired.com/2008/01/ff-iphone/

- http://www.networkworld.com/article/2159873/smartphones/apple-s-iphone–the-untold-story.html

- http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/06/magazine/and-then-steve-said-let-there-be-an-iphone.html?pagewanted=1&_r=1&smid=tw-share&

- http://archive.fortune.com/2007/01/10/commentary/lewis_fortune_iphone.fortune/index.htm

- http://money.cnn.com/galleries/2011/technology/1109/gallery.apple_financial_empire/5.html

- https://9to5mac.com/2011/10/21/jobs-original-vision-for-the-iphone-no-third-party-native-apps/

- http://allthingsd.com/20120803/apples-phil-schiller-on-how-apple-came-up-with-the-iphone-and-ipad/

- http://www.dazeddigital.com/artsandculture/article/33692/1/discussing-design-with-the-man-behind-your-iphone?curator=MediaREDEF

- http://www.macworld.com/article/2047342/remembering-the-newton-messagepad-20-years-later.html

- http://www.nytimes.com/1993/12/12/business/marketer-s-dream-engineer-s-nightmare.html

- http://www.imore.com/apple-senior-vice-presidents-phil-schiller-and-scott-forstall-share-brief-pre-history-iphone-and

- http://www.theverge.com/2012/8/3/3218164/scott-forstall-testimony-apple-v-samsung-trial/in/2971889

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qf9XcNWRvSU&feature=youtu.be&t=31m10s

Love the podcast. Just a note that the pronunciation of the Motorola Rokr is “rocker” as in “rock music”.

Yeah, I amended a correction halfway through the episode. If you downloaded within the first 6 hours, you won’t hear the correction. But all subsequent downloads will have it. In my 120+ episodes, this is the oddest error I’ve made. I even re-watched the Rokr launch video! But somehow, in my head, every time I read it, it felt like it should be pronounced the way I pronounced it. Odd screwup, but thanks for the catch!

[…] McCullough / Internet History Podcast:The History of the iPhone, On Its 10th Anniversary — So… Three things: A widescreen iPod with touch controls. A […]

[…] McCullough / Internet History Podcast:The History of the iPhone, On Its 10th Anniversary — So… Three things: A widescreen iPod with touch controls. A revolutionary mobile […]

[…] hörenswerter Rundumschlag für den heutigen Tag ist The History of the iPhone, on its 10th anniversary von Brian McCullough. Es ist eine ganze Podcaststunde mit vielen kleinen Details rund ums […]

[…] McCullough, Internet History Podcast: Every time you see someone, head down, engrossed in their phone, it’s worth realizing that […]

[…] och hur presentationen genomfördes är på många sätt spektakulär (jo, på riktigt!), och Internet History Podcast har gjort ett fantastiskt arbete med att grotta ner sig i historien. Här finns såväl bakgrunden […]

[…] Source: The history of the iPhone, on its 10th anniversary […]

[…] Internet History Podcast: The History of the iPhone How we got from Newton to iPhone. Also, the ROKR was a thing. […]

Ten years is a pretty long time in terms of tech. It’s funny how most tech critics believed the iPhone wouldn’t even last an entire year before it failed. The iPhone was said to be too expensive and made by a company which knew nothing about the cellular phone business. I’m willing to bet those people are still around wishing and hoping the iPhone will fail horribly on its eleventh year. I bet everyone of those who predicted the iPhone would fail have a smartphone in their pocket that they use every day.

[…] it all looks so slick that it’s hard to believe just how close it came to falling over. The Internet History Podcast has done a nice job of pulling together the inside story of how much preparation went into ensuring […]

[…] falar na apresentação em si, sugiram algumas informações interessantes, conseguidas pelo The Internet History Podcast, sobre a preparação de Steve Jobs e sua […]

[…] For an in-depth look back at the first iPhone, tune in to this great episode of the Internet History Podcast. […]

[…] For an in-depth look back at the first iPhone, tune in to this great episode of the Internet History Podcast. […]

[…] it all looks so slick that it’s hard to believe just how close it came to falling over. The Internet History Podcast has done a nice job of pulling together the inside story of how much preparation went into ensuring […]

[…] it all looks so slick that it’s hard to believe just how close it came to falling over. The Internet History Podcast has done a nice job of pulling together the inside story of how much preparation went into ensuring […]

[…] For an in-depth look back at the first iPhone, tune in to this great episode of the Internet History Podcast. […]

[…] For an in-depth look back at the first iPhone, tune in to this great episode of the Internet History Podcast. […]

[…] The Internet History Podcast lässt die Männer zu Wort kommen, die kurz vor der Präsentation des ersten iPhones 2007 in San Francisco hinter der Bühne standen und zitterten… […]

[…] ‘The Best 1.0 in Tech History’ […]

[…] fue la frase con la que Steve dió el pistoletazso de salida de la Keynote. Pero según comentan en Internet History Podcast, Steve preparó la presentación durante 6 días, pero a última hora, el equipo de ingenieros aún […]

[…] fue la frase con la que Steve dió el pistoletazso de salida de la Keynote. Pero según comentan en Internet History Podcast, Steve preparó la presentación durante 6 días, pero a última hora, el equipo de ingenieros aún […]

[…] con la que Steve dió el pistoletazso de salida de la Keynote. Pero según comentan en Internet History Podcast, Steve preparó la presentación durante 6 días, pero a última hora, el […]

[…] For an in-depth look back at the first iPhone, tune in to this great episode of the Internet History Podcast. […]

[…] reliance on web apps and brought with it the App Store. For more on the history of the iPhone, this post from the Internet History Podcast is well worth a […]

[…] fue la frase con la que Steve dió el pistoletazso de salida de la Keynote. Pero según comentan en Internet History Podcast, Steve preparó la presentación durante 6 días, pero a última hora, el equipo de ingenieros aún […]

[…] For an in-depth look back at the first iPhone, tune in to this great episode of the Internet History Podcast. […]

“On their first attempt, the team at Apple managed to stumble upon the perfect form factor, the perfect incarnation of the modern smartphone.”

They had a bunch of counterexamples already of how not to build it. They took the time to design it. I wouldn’t call time spent designing “stumbling”.

There are lots of examples of this happening in other industries, too. Honda invented the modern motorcycle with the CB750 in 1969, and the form has barely changed in almost 50 years. Canon invented the modern SLR with the AE-1 in 1976, and only change in recent years came with the move to a digital sensor (though the overall form has remarkably stayed the same). The Tucker ’48 had liquid cooling, fuel injection, independent suspension, seatbelts, and disc brakes, a thoroughly modern car in features, if not styling or performance.

It’s always satisfying to see a watershed new machine, but it’s not the first time for such a machine to have been created all at once. All you need is an effective team who understands the technology and the users.

[…] 雷锋网按:十年前的 1 月 9 日,苹果推出第一代 iPhone,重新定义手机,自此带我们进入了智能手机时代。十年后的今天,让我们一起回望这款科技史上伟大产品的诞生历程。本文由雷锋网编译自 Internet History Podcast,原文作者Brian Mccullough。下半部链接:点我。 […]

[…] ist übrigens, dass das iPhone bei der Keynote nur ein Prototyp war und bei weitem nicht marktreif. Verschiedene Tricks mussten eingesetzt werden, damit die Präsentation reibungslos […]

[…] مدونة Internet History Podcast تقريرًا استعرضت فيه مؤتمر آبل الذي كشفت فيه للمرّة الأولى عن […]

[…] The History of the iPhone, On Its 10th Anniversary, http://www.internethistorypodcast.com […]

[…] Source:Internet History Podcast via 9to5Mac […]

[…] nachdem man sich bei Apple Mitte 2005 dazu entschlossen hatte, die bereits angelaufenen Arbeiten an einem Tablet zu Gunsten des ersten iPhones ruhen zu lassen um die Idee eines […]

[…] For an in-depth look back at the first iPhone, tune in to this great episode of the Internet History Podcast. […]

[…] July 2008, Apple introduced the App Store, and the popularity of the native mobile app development quickly skyrocketed from there. The idea […]

[…] years ago, Apple announced the iPhone, which soon gave birth to the App Store and the resulting broader app ecosystem. That […]

[…] informe de 2013 del New York Times Magazine , corroborado por The Internet History Podcast esta semana, reveló cómo el iPhone era tan increíblemente defectuoso que era muy probable que […]