Remember this?

So, three things: a widescreen iPod with touch controls; a revolutionary mobile phone; and a breakthrough Internet communications device. An iPod, a phone, and an Internet communicator. An iPod, a phone— are you getting it? These are not three separate devices. This is one device, and we are calling it iPhone. Today, Apple is going to reinvent the phone.

– Steve Jobs, January 9, 2007

It turns out that almost exactly 9 years before Steve Jobs spoke those words and introduced the world to the iPhone, there was another 3-in-1 device that was introduced to the world, and it just so happened that that device was also known as an iPhone.

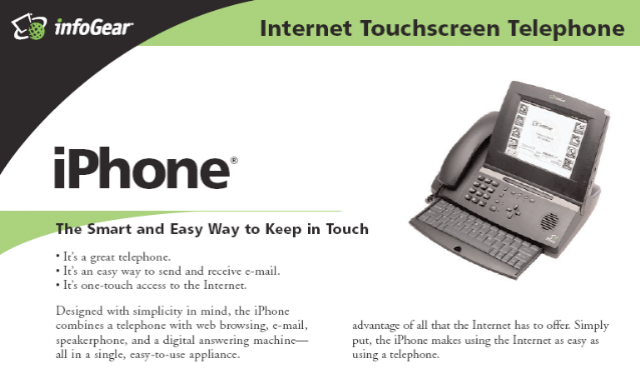

But the company that brought the “first” iPhone to market, all the way back in 1998, was called InfoGear, not Apple.

Here’s the story…

The iPhone that came before Apple’s iPhone

In the late 1990s, there was a fad for devices called “Internet appliances.” The idea was to have smaller, purpose-designed devices that would allow users to jump on the web and do web things without having to whip out a laptop or a PC. Remember, this was back in the day when laptops could still be 10 pound affairs.

So, the industry envisioned smaller devices that you could put on your desk, in your kitchen, maybe on your wall, that would allow you to check your email, browse the web, as a quick and easy, in-and-out affair.

A skunkworks project for just such an “appliance” was started in 1995, inside, of all places, National Semiconductor. Three engineers, Chaim Bendelac, Yuval Shahar and Reuven Marko were given company funds to explore the possibilities for a product that would be part internet, part telephone. They called their brainstorm “Project Mercury.”

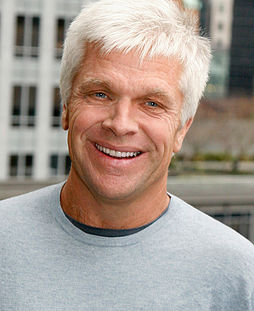

At around the same time, a venture capitalist by the name of Robert Ackerman, was consulting with National Semiconductor. Toward the end of a routine meeting, Ackerman’s hosts offered to show him around the engineering lab. It was there that Ackerman would first see Project Mercury.

“The team had taken an 8-bit processor that they had used in fax machines and basically built a very crude prototype device—but a functioning prototype device—with a proprietary little browser that would allow you to browse the web,” Ackerman remembers today. “We saw that project and I said, ‘That’s the future!'”

As he recounted later in a blog post, “It looked like something my 11-year-old would build by running through the junk yard collecting pieces. When I was told it was a telephone integrated with a Web browser and a screen, I had an “Aha” moment. The ragtag collection of circuit boards lying in front of me had the makings of exactly the sort of post-PC Web-based computer that Silicon Valley’s keenest minds were beginning to predict.”

Ackerman was so enthused by the project that he decided to extricate the technology from National Semiconductor’s lab and use it as the foundation to launch a standalone business, which would become InfoGear Technology Corporation. Obviously, Ackerman would need to convince National Semiconductor to release not only to the technology associated with Project Mercury, but also the engineers who had dreamed it up.

The negotiations were, according to Ackerman, difficult. But things were resolved in the end by the direct intervention of National Semiconductor’s then-president, Gilbert Amelio. In what would be the first of many ironic parallels with the eventual Apple iPhone, Gil Amelio would very shortly become CEO of Apple, and it would be Amelio who would purchase NeXt, thereby bringing Steve Jobs back to Apple. Amelio signed off and allowed the InfoGear iPhone to come to life, but he also put into place the pieces that allowed the Apple iPhone to be developed years later.

Project Mercury Becomes the iPhone

It seems that very early on in the development process, the new all-in one device acquired the name iPhone, complete with the lower-case “i” and upper-case “P,” just as with Apple’s later invention.

Ackerman explained the nomenclature like this:

“The way we came at it is, we looked at the telephone as being the original information appliance. This was the evolution of the original information appliance—on steroids. So, iPhone was internet-phone… information-phone.”

But there were other antecedents for the iName convention. Most famously, around the same time in the 1990s, there was the community website iVillage, which would have a storied IPO and would eventually be purchased by NBC (NBC’s one-time internet efforts were, coincidentally, called NBCi). One of the founders of iVillage, Robert Levitan, recently told me that iVillage had lifted the naming convention specifically from the iGolf channel on AOL, but that they were also inspired by similar “iCommunities” on places like AOL and Prodigy.

There were other startups from the dotcom era with names like iManage and iPrint. And there was a similar fad at the time for eNames. For example, Apple’s brief AOL-competitor was called eWorld. There was eToys.com and Epinions.com, as well as many others.

Aside from the naming similarities, though, InfoGear’s iPhone would have plenty of other eerie similarities to Apple’s later device, both philosophically and technically.

For one thing, just as in Steve Job’s famous mantra, the InfoGear iPhone was designed to do three core things (phone calls, email and light web browsing) but to do them well. And from the very beginning, there was an almost Apple-like obsession with simplicity and ease of use. Interested in presenting an approachable, consumer-friendly image, InfoGear hired Frog Design, famous for the previous industrial design of various Apple and Mac computers.

“Our design criteria was, could my mother use it?” Ackerman remembers. “If you could use a telephone and use an ATM, that was the skill set that should be required in order to engage with the Internet.”

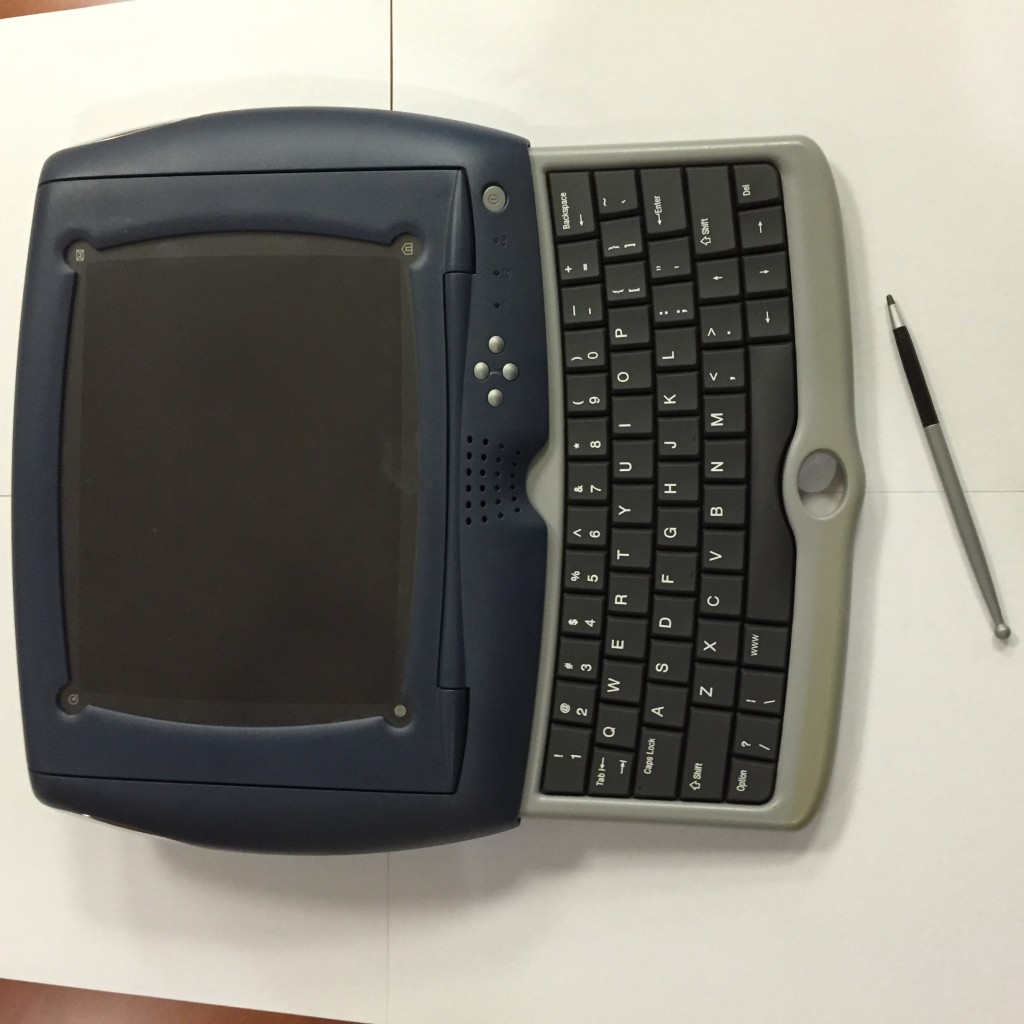

Just as interestingly, even though the iPhone offered a paired down, slide-out physical keyboard, its prominent mode of user interaction was a small, black-and-white LCD touchscreen, similar to ATM screens that existed at the time. As you can see from these photos, things like email and the web were accessible by graphical icons that the user could tap on to launch. Sound familiar?

Touch-enabled LCD screens were still such an immature technology that they actually presented InfoGear with something of a problem. The company had hoped that the “bill of materials,” the cost of manufacturing each iPhone unit, would top out at $100. This would enable the company to market the iPhone in the $250 to $300 range. But each seven-inch, 640 X 480 greyscale touchscreen alone came in at $80 a pop.

So, much as cell-phone makers learned to get telecom companies to subsidize the cost of handsets on behalf of consumers, InfoGear began seeking out a partner that would subsidize the cost of the iPhone. Unfortunately, despite making the rounds to the Baby Bells and even cable companies, InfoGear was never able to nail down a deep-pocketed partner.

“We would sit down and talk to the telephone companies,” remembers Ackerman, “You’d talk about this converged device that was the intersection of the web and telephony, and they would look at you like you had three eyes. ‘But the telephone is the telephone and the internet is the internet!’ You just simply could not have the conversation around these two worlds coming together.”

And thus, when the device was unveiled to the public at CES in early 1998, it carried a price tag of $499 with a separate $19.95 charge for Internet access.

Despite this high-end price point, early reviews of the iPhone were nothing short of enthusiastic. Personal Computer World called the iPhone “an exciting look at the future of telephony integration.” PC World described it as “a well-designed product” that “smoothly combines phone, Internet, and e-mail access in one small console.” The iPhone won an Innovations ’98 award from the 1998 CES and a Best of Show award for Outstanding Desktop Hardware Product at Fall Internet World ’98.

And all of this came in spite of the device’s limitations. Because the first iPhone only had one phone line, users couldn’t make a call and browse the web at the same time, something that Apple’s eventual iPhone had no problem with. The unit had a measly 16-bit processor, and the entire iPhone only had one megabyte of total memory. For the entire unit.

“We were constrained, not by vision, but by the availability of technology,” Ackerman says. “That really defined what we could do.”

In spite of these limitations, the InfoGear iPhone was not only a forward thinking “converged” device, it had true innovations all across its product offering. Among them:

- Very early use of touch technology. Whenever a web page displayed a phone number, the iPhone automatically turned the number into a touch-screen button, allowing the user to dial just by touching the screen.

- Because the device was so constrained, the bulk of the processing was dumped back on a server, in an early model of what we would now call “cloud computing.”

- The Apple iPhone famously launched with visual voicemail, but the InfoGear iPhone had something similar. Voice messages were transcribed and showed up on the screen along with a button that allowed you to automatically dial and return the call.

- The InfoGear iPhone had a maps application with data provided by RR Donnelley & Sons.

- It offered movie listings from Hollywood Online.

- It had a Newsstand-like feature providing content from Time Inc.’s family of magazines, including People, Time, Money, and Sports Illustrated.

An early InfoGear press release stressed that the iPhone would not replace the PC, but instead would “co-exist with PCs much as the microwave co-exists with a conventional oven.”

Sort of like Steve Jobs’ eventual “cars vs. trucks” metaphor. A post-PC message in the pre-post-PC era.

How the iPhone Name Passed to Apple

InfoGear intended for the iPhone to be the vanguard of an entire family of products with color screens, video conferencing, Voice-Over-IP, etc. And indeed, there was an iPhone 2 released in 1999, complete with a second phone line and a redesigned keyboard, which Industry Standard magazine said was “closest to the brass ring” when it came to Internet Appliances.

Over the course of the product line, it is estimated that approximately 100,000 iPhones were sold. There’s even a product listing still visible on Amazon that you can view. It says that the product is “currently unavailable.”

But in the end, the fad for Internet Appliances proved to be, just that, a fad. A Wall Street Journal article from 1998 headlined: “The Future Calls: Smart phones have lots of cool features—but not all that many customers.”

Robert Ackerman simply thinks that the InfoGear iPhone was a product ahead of it’s time. “Over my career, I’ve seen numerous instances where you identify an opportunity and you develop a concept around that opportunity to do something that’s truly disruptive in the marketplace. The problem is that sometimes that vision is ahead of the market.”

But before the iPhone could be consigned to the dustbin of history, one of InfoGear’s later-round investors, Cisco, came to the rescue and gave the technology a home. Cisco was just beginning to embark on a push toward consumer-facing hardware, an effort that would lead famously (or infamously) to the eventual purchase of router-maker Linksys as well as the Flip video camera. So, at the apex of the dot-com era, in March of 2000, Cisco offered $300 million in stock to purchase InfoGear. The offer was happily accepted.

And thus, the iPhone technology—or, more crucially, the iPhone name and trademark—passed on to Cisco. Cisco would briefly use the iPhone name to market a line of VOIP telephones under the Linksys brand.

When Apple finally announced its iPhone in early 2007, Cisco briefly sued Apple for trademark infringement. The negotiations were not without some classic Steve Jobs-style negotiation “tactics” but eventually, Cisco agreed to allow Apple to use the iPhone moniker going forward.

Bob Ackerman is sanguine about the iPhone name living on, because in a way, it represents his original notion of a converged, all-in-one device living on.

“I can look at where things are today and I find a level of satisfaction in that,” Ackerman says. “I would be less than honest if I didn’t say there wasn’t some frustration that goes with that satisfaction. You know, if only we had gotten the timing a little bit better. (…) Right idea. And directionally correct. Eventually, that’s where the market went. But we were just too early. (…) The architecture was right, the vision was right… product name was pretty good… intellectual property was right on the money! We were early into the marketplace. Ten years later, a very different story.”

The rest, as they say, is history.

Except, there’s one more thing…

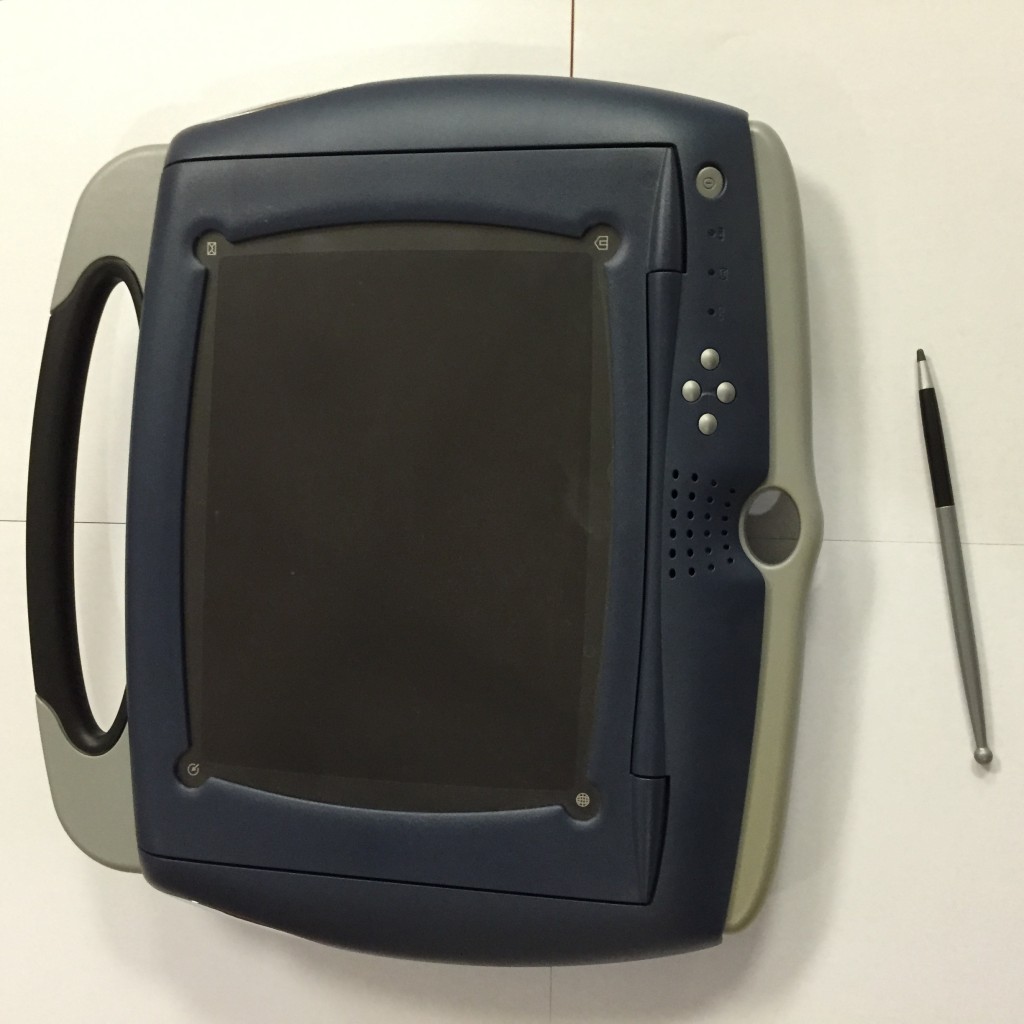

InfoGear Designed an iPad Also!

“We’ve never talked about it,” Bob Ackerman says, “But we actually did a wireless device that was called the iPad. We created a prototype. Never took it to the market, but it was a concept piece that we dubbed our ‘iPad.’ This was post-Newton having come out from Apple, as kind of the ‘pad,’ the personal digital assistant, as they were called at that point in time. We built a device that was a touchscreen with a stylus, that was to connect wirelessly. It was a concept piece. We dubbed it the iPad.”

Updated!

Thanks to Bob Ackerman, we now have photos of what the InfoGear iPad prototype actually looked like:

[…] The Forgotten Story of the Original iPhone Released in 1998 […]

I’ll bet they made more money selling the name to Apple than selling their silly device.

[…] „The forgotten story of the original iPhone released in 1998“ […]

[…] het hele verhaal van de iPhone uit 1998 wilt weten, kun je het beste dit artikel van Brian McCullough doorlezen. Eind jaren 90 was er een gekte rond internet-apparaten. Laptops waren zwaar en mensen […]

[…] here’s their playlist of 200 “Songs We Love” from 2015. The forgotten story of the original iPhone released in 1998. Finally, for your entertainment, I give you A Ship to Ship […]

[…] this as a backdrop, the Internet History Podcast recently took a look back at the original iPhone, a product which, believe it or not, Infogear launched all the way back in […]

[…] this as a backdrop, the Internet History Podcast recently took a look back at the original iPhone, a product which, believe it or not, Infogear launched all the way back in […]

[…] this as a backdrop, the Internet History Podcast recently took a look back at the original iPhone, a product which, believe it or not, Infogear launched all the way back in […]

[…] this as a backdrop, the Internet History Podcast recently took a look back at the original iPhone, a product which, believe it or not, Infogear launched all the way back in […]

[…] The Internet History Podcast via BGR […]

[…] conociera de primera mano el Proyecto Mercurio. Nada más ver los primeros prototipos lo vio claro. “¡Eso es el futuro!”, recuerda que exclamó. Tal era el potencial que vio que aquel producto que se propuso sacarlo del laboratorio de National […]

[…] It was released in 1998, and sat on your desk. […]

[…] Internet History Podcast, CNN, Cnet, Wikipedia This entry was posted in Phone Reviews on June 20, 2016 by […]

[…] conociera de primera mano el Proyecto Mercurio. Nada más ver los primeros prototipos lo vio claro. “¡Eso es el futuro!”, recuerda que exclamó. Tal era el potencial que vio que aquel producto que se propuso sacarlo del laboratorio de National […]

[…] revealed in an intriguing article by the Internet History Podcast, the InfoGear iPhone grew out of a skunkworks project at National Semiconductor called “Project […]

[…] the 1997 iPhone, Robert Ackerman, a venture capitalist who pushed for the independence of InfoGear, said: “We were early into the marketplace. Ten years later, a very different story.” By contrast, […]

[…] the 1997 iPhone, Robert Ackerman, a venture capitalist who pushed for the independence of InfoGear, said: “We were early into the marketplace. Ten years later, a very different story.” By contrast, […]

[…] the 1997 iPhone, Robert Ackerman, a venture capitalist who pushed for the independence of InfoGear, said: “We were early into the marketplace. Ten years later, a very different story.” By contrast, […]

[…] the 1997 iPhone, Robert Ackerman, a venture capitalist who pushed for the independence of InfoGear, said: “We were early into the marketplace. Ten years later, a very different story.” By contrast, […]

[…] the 1997 iPhone, Robert Ackerman, a venture capitalist who pushed for the independence of InfoGear, said: “We were early into the marketplace. Ten years later, a very different story.” By contrast, […]

[…] the 1997 iPhone, Robert Ackerman, a venture capitalist who pushed for the independence of InfoGear, said: “We were early into the marketplace. Ten years later, a very different story.” By contrast, […]

[…] the 1997 iPhone, Robert Ackerman, a venture capitalist who pushed for the independence of InfoGear, said: “We were early into the marketplace. Ten years later, a very different story.” By contrast, […]

[…] the 1997 iPhone, Robert Ackerman, a venture capitalist who pushed for the independence of InfoGear, said: “We were early into the marketplace. Ten years later, a very different story.” By contrast, […]

[…] revealed in an intriguing article by the Internet History Podcast, the InfoGear iPhone grew out of a skunkworks project at National Semiconductor called “Project […]

[…] revealed in an intriguing article by the Internet History Podcast, the InfoGear iPhone grew out of a skunkworks project at National Semiconductor called “Project […]

[…] revealed in an intriguing article by the Internet History Podcast, the InfoGear iPhone grew out of a skunkworks project at National Semiconductor called “Project […]

[…] revealed in an intriguing article by the Internet History Podcast, the InfoGear iPhone grew out of a skunkworks project at National Semiconductor called “Project […]

[…] revealed in an intriguing article by the Internet History Podcast, the InfoGear iPhone grew out of a skunkworks project at National Semiconductor called “Project […]

[…] iPhone was born in a National Semiconductor lab as a skunkworks project, Brian McCullough writes on Internet History Podcast. The company had granted funds to engineers Chaim Bendelac, Reuven Marko, and Yuval Shahar to work […]

[…] iPhone was born in a National Semiconductor lab as a skunkworks project, Brian McCullough writes on Internet History Podcast. The company had granted funds to engineers Chaim Bendelac, Reuven Marko, and Yuval Shahar to work […]

[…] was born in a National Semiconductor laboratory as a skunkworks task, Brian McCullough composes on Web History Podcast The business had actually approved funds to engineers Chaim Bendelac, Reuven Marko, and Yuval […]

[…] Zdroj: internethistorypodcast.com […]

[…] iPhone was born in a National Semiconductor lab as a skunkworks project, Brian McCullough writes on Internet History Podcast. The company had granted funds to engineers Chaim Bendelac, Reuven Marko, and Yuval Shahar to work […]

[…] http://www.internethistorypodcast.com/2015/06/the-forgotten-story-of-the-iphone-released-in-1998/ […]